|

|

The Irish invented Chess! I kid you not... international |

history and heritage |

opinion/analysis international |

history and heritage |

opinion/analysis

Sunday December 27, 2009 23:38 Sunday December 27, 2009 23:38 by Brian by Brian

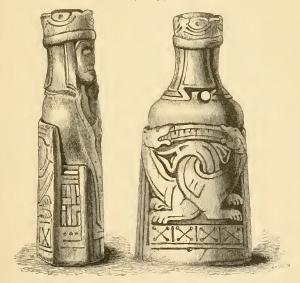

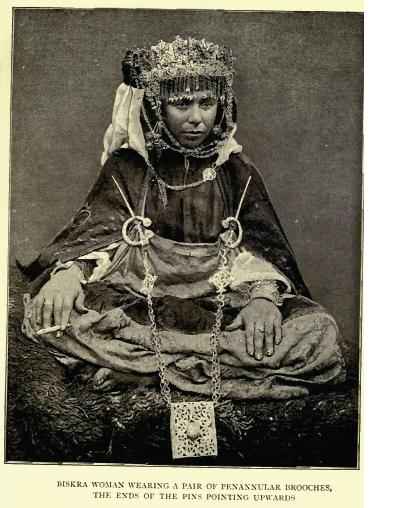

Every secret of art, every subtlety of knowledge, and every diligence of healing that exists, from the Tuatha De Danann had their origin. And although the Faith came, these arts were not driven out, for they are good.(1) References in the old stories and histories of Ireland "Good," says Guaire, "Let's play fidchell."Another reference, this time from Serlige Con Chulaind: 'Behold his chariots, they climb the valley; behold their courses, (like) men in fidchell'.(3)From Amra Columcille: "Crimthann Nia Nar's fidchell, a small boy could not lift it with one hand. Half of its men were of yellow gold, the other half of tinned bronze." (4)Finally from the poem beginning "Abair riom a Eire ogh," attributed to Maoil Eoin Mac Raith and using the word brannaimh for chess: "The centre of the plain of Fal is Tara's castle, delightful hill; out in the exact centre of the plain, like a mark on a parti-coloured brannumh board. Advance thither, it will be a profitable step: leap up on that square, which is fitting for the branan, the board is fittingly thine. I would draw thy attention, o white of tooth, to the noble squares proper for the branan (Tara, Cashel, Croghan, Naas, Oileach), let them be occupied by thee. A golden branan with his band art thou with thy four provincials; thou, O king of Bregia, on yonder square and a man on each side of thee."(5) If you add those clues up you get a board with equal numbers of men on each side, and set up with different colours for the two sides like modern chess, the king, who is one of the pieces and other pieces are called 'men', could with profit aim for maybe the central squares, but protected by men around him, that sometimes the 'men' - evidently the pawns - can block the advance of their opponents and can be difficult to kill, and that the advance of the 'men' in chess is like the advance of chariots on a battle field. This last reference is arguably the most valuable, those chariots must have advanced in a military line like you'd see in films of Waterloo or whatever, because that way each soldier gets room to engage the enemy by firing spears etc, if they advanced in a column the person in front would get in the way, and in any case clearly the chariot wheels would create rivets in the ground that would impede those coming after them. The point is that this is very like the advance of pawns in chess and not at all like other games such as backgammon or draughts etc. On the other hand there is nothing there to link it to the latter two games, no mention of dice, no mention of multiple kings on the same side, and many other games, such as the fox and geese type, do not start with equal forces. Then there is the most important single reference in old Irish manuscripts, the entry under fidchell in Cormac's Glossary. Cormac, the Bishop of Cashel who died in 908, wrote this dictionary like glossary to explain some of the older Irish words then currently existing but going obsolete. It reads: "Fidchell .i. féthciall. fáthciall .i. ciall & fath ocahimbirt. no fuathcell .i. fuath cille .i. cetharcoir cétamus infhidchell & dirge a títhe. dub & find forri & sainmuintir cach la fecht beos bereas a cluithe. Síc et ecclesia per singula per .IIII. terrae partes .IIII. evangeliis pásta. isdirech ambesaib & hitíthib nascreptra et nigri et albi .i. boni et mali habitant in ecclesia."(6)This mixture of Irish and Latin has been translated as: "Fithchill, i.e. cause-sense. i.e. cause and sense (are used) in playing it. Or sinew and sense. Or fuath-cell, i.e. shape of a church, i.e. the fithchill (board) is four-sided in the first place, and its rows are straight, and (there are) black and white on it, and it is a different person who wins (?) every other time. So also the church in all particulars: fed by four gospels in the four quarters of the earth (i.e. it is thus in the church filling the four respective parts of the world with the Gospels); it is straight [i.e. 'upright'?] in judgements with the rows of scripture; i.e. black and white, i.e. good and bad live in the church." (7)Slightly ambiguous I guess but nonetheless its usually understood to mean "that the chessboard was divided into black and white compartments by straight lines: that it is to say into black and white squares," as P W Joyce points out in that quote. (8) The reference to winning the game in turns could easily be to the practice of playing the white pieces every other game? Apart from a few other stray references that add one or two points (such as the point that the set probably includes men who are sometimes represented with human faces or bodies, because one poetic reference in the old tales seems to suggest this,(9) which is obviously not the case with backgammon or draughts, and secondly that it was represented in the literature as being related to battle tactics, because Brian Ború's son is said to have mocked a person's military skill due to their weakness at fidhchell (10)) that is pretty much where we are at in our understanding of the Irish game of fidhchell or brannaimh.(11) Which brings us to the current impasse. What is effectively happening now is that Irish historians are being told that it is impossible for modern style chess to be played as long ago as the Irish stories claim, because it is said that chess was brought across into Europe from Persia or India at a much later date to the Irish histories, and are kind of being bullied into representing it as draughts or backgammon or just "chess-like" to accommodate this - Indian! - sacred cow of chess history! (12) But in fact there are other Irish words that sometimes represent different games like those, e.g. taipleis, meaning tables, usually understood as draughts and sometimes backgammon (13), or buainbeg (14), or the game described by an Irish scribe in the 10th century and sometimes called 'The Game of the Gospel'. (15) Meanwhile the Irish always claimed that fidhchell and brannaimh meant chess, not these other games, so if it could be proven that the lexicographical history of those two words universally meant chess over the centuries from Medieval times right down to modern Irish, or indeed if the entries link these two words with the international game of chess, then maybe people will take more seriously the idea that the ancient Irish were in fact playing modern style chess. (16) To illustrate this we can go back as far as 1512: Fidhchell and Brannaimh, lexicographical history c.1512 There is this reference in the account of the The Second Battle of Moytura contained in Harleian Ms 5280, a vellum manuscript held in the British Museum: "This he the king said then, that the chessboards of Tara should be fetched to him Samildánach and he won all the stakes, so that then he made the Cró of Lugh."In a way this is just another reference to fithchell but here the scribe, Giolla Ríabhach (Mór) Ó Cléirigh, writing in c.1512, adds this gloss, or footnote: "But if chess was invented at the (epoch) of the Trojan war, it had not reached Ireland then, for the battle of Moytura and the destruction of Troy occurred at the same time." (17)As Eoin Mac White noted in 1945 this shows that O'Cleírigh had associated the word fidhchell with the international game of chess, because the connection of chess with Troy came from a popular book circulated in England a few centuries before, the Troy reference does not come from Irish traditions or sources. (18) c.1631 The great Seathrun Ceitinn, or Dr Geoffrey Keating, the author of the most popular History of Ireland in the Irish language, wrote a book in c.1631 called in English 'The Three Shafts of Death', from which the following extract might be of interest: "Ionnus gurab ionann dál do na daoinibh i gcoitchinne 7 d'fhuirinn an bhrannaimh: óir mar bhíos barr ceana seoch a chéile ar fhearaibh foirne an bhrannaimh ré linn bheith ag imirt orra, ionnus go mbí rí na foirne arna shuidhiugadh san áit is onóraighe don chlár, 7 an bhain-ríoghan san dara háit, 7 mar sin do gach fear oile do réir a gharma ionadtar ar chlár an bhrannaim é; mar an gcéadna dona daoinibh, an tan bhíd ar títhibh na talmhan, 7 bearta brannaimh na beata agá n-imirt leó, bí gach aon aca go cinnte na ionadh féin do réir a onóra 7 a innmhe. Gidh eadh, tuigthear, tar ceann go mbí an t-eidirdhealughadh úd idir fhearaibh foirne an bhrannaimh ré mbeith ag imirt leó, an tan bhíos an cearrbhach agá gcor i mála na foirne, go ndoirteann imeasg a céile iad, gan féachain d'fhior dhíobh seoch ar-oile, ionnus gur cuma leis tús nó deireadh dholta san mhála do bheith ag an rí, seoch an bhfior is lugha san bhfuirinn; 7 fós is cuma leis cia dhíobh bhíos i n-uachtar nó i n-íochtar an mhála. Mar an gcéadna theaghmas dona daoinibh; an tan tig buachaill brannaimh na beatha .i. an bás, 7 teilgeas na daoine i dtiaich na talmhan do chlár tháiplise an tsaoghail, ní bhí onóir ag an mbás i gcomhair aoin seach a chéile dhíobh. Agus dá dtugadaois lucht an díomusa da n-aire an coimhmeasgadh so do-bheir an bás ar na daoinibh, do thréigfidís a n-uaill 7 a n-ainmhiana."A suggested translation is: "So that it is the same for people in general as for a team in brainnaimh: since we are together in the top position [on the board] in the team of brannaimh men, when we are ready to play with them, so that the king of the team is placed in the seat of most honour on the board, and the queen in the second place, and like that for each of the other men according to the position on the brannaimh board; and similiarly for people, the time we are on the chequered [thíthibh] ground, playing the brannaimh of life with them, each one of us is certainly in our own place as regards honour and ability; howbeit, notwithstanding that though, we give that distinction to the different men of the brannaimh team only when we are playing with them, at the time that the gambler is putting the team in the bag, pouring them all in together, he doesn't look at one man of them beyond another, so that it is immaterial to him if the king goes into the bag first or last, and the same for the least man of the team; and as well its the same to him whether they are on the top or the bottom of the bag. The same way it befalls people, the time that the brannaimh boy comes from the world .i.e. dies, the person falls into the bag of the earth from the draughts [táiplisi] board of life, there is no honour in the death above that of any of them. And if the prideful masses would give heed to how comparable this was to the makings of death in people, they might forsake their pride and evil desires." (19)It might be safe enough then to agree with Eoin Mac White when he says that this brannaimh "is clearly modern chess." (20) Although Keating normally uses fidhchell to describe chess in his history, nonetheless he does use the word brannaimh to describe a boardgame played among the old Irish, hence Dr Keating can be scribbled down as a witness that the game the old Irish were playing was indeed our modern chess. (21) 1685 Roderic O'Flaherty is often considered a link between the more modern historians and the old Irish bardic schools that he was acquainted with in the west. He wrote a history of Ireland in Latin in 1685 called Ogygia and therein translated no.5 in the will of a 2nd century Irish king, Cathaoir Mór, thus (22): "duas schacchias cum latrunculis, suis maculis distinctis". In English that is: "two chess-boards with their men, distinguished with their specks". Notice that he uses 'schacchias' for the chess-board, which is very like scacus, -i, the recognised Latin for the word 'chess'. And 'latrunculis' is also a very familiar Latin term for chessmen. Therefore again, as far as he is concerned, the old Irish game was the modern chess. (23) 1694 One of the first great chess historians was Dr Thomas Hyde, from Oxford, who wrote in Latin in the last years of the 17th century. His account includes the following reference to the Irish: "The old Irish were so greatly addicted to chess, that, amongst them, the possession of good estates hath been decided by it; and there are some estates at this very time, the property whereof doth still depend upon the issue of a game of chess. For example, the heirs of two certain noble Irish families, who we could name, (to say nothing of others) hold their lands upon this tenure, viz. that one of them shall encounter the other at chess, in this manner, that which ever of them should conquer, should seize and possess the estate of the other. Therefore, I have been told, they manage the affair prudently among themselves; once a year they meet by appointment to play at chess: one of them makes a move, and the other says, I will consider how to answer you next year. This being done a public notary commits to writing the situation of the game, by which method a game, which neither hath won, hath been, and will be continued for some hundreds of years." (24)So again he is saying that the old Irish game was our game of chess. This is enormously significant because his book is about chess, hence if he knew of any difference between the Irish game and the normal one you would expect him to talk about it, and note that the quote shows that he clearly did do some research into the Irish game. 1732 One of the very early printed dictionaries was Conor Begly and Aodh Buí MacCurtain, The English Irish Dictionary (Paris, 1732): "Chess, brannamh, sórt imeartha [type of game] Draughts, sórt imeartha [notice they do not include brannamh here, unlike under chess]." 1768 This work involves two bishops, the first Fr John O'Brien, the Catholic Bishop of Cloyne who wrote a dictionary published in Paris in 1768, and secondly the Rev Robert Daly, the Church of Ireland Bishop of Cashel who updated and reissued the dictionary (full of compliments towards the previous author) in Dublin in 1832. Both authors went with: "Brannumh, chess, a game played upon a square board divided into sixty-four small chequers: on each side there are eight men and as many pawns, to be moved and shifted according to certain rules; an fitcheall acus an brannamh ban, (Old Parchment,) probably means the men; gon a bhranaibh déad, with his ivory men, because made of elephant's teeth. This was a favourite game with the old Irish. Lat. scacharum ludus. Fithchill and fithchille, tables, or chess-board; ag imirt fithchille, playing at tables, or chess." (25) 1780 Rev William Shaw, A Galic and English Dictionary (London, 1780), vol 1: "Brannamh, Chessmen Fitchill, fitchille, Tables, chess-board." 1782 General Charles Vallancey combined engineering in Ireland with some historical researches, including this very early Irish Grammar and Phrase Book called A Grammar of the Hiberno-Celtic or Irish Language (Dublin, 1782), p.84: "Phill, Fithill, Fitchill, a chess-board, also the game of chess." 1786 Charlotte Bronte was famous as a great collector of poems and stories among the Irish in Co. Cavan in the 18th century, and she translated in 1786 a verse that included fithchioll as: "Or on the chequer'd fields of chess Their mimic troops bestow'd;" (26) 1814 Working in the early days of modern Gaelic scholarship, Thaddaeus Connellan, a pioneer in attempting to translate the Annals of the Four Masters, came out with An English-Irish Dictionary in Dublin in 1814: "Chess, branamh." 1817 Edward O'Reilly, who ran a shop in Dublin but whose ancestors came from Corstown in Co. Meath, wrote a well known dictionary in 1817. He personally owned a huge number of old Irish manuscripts and brought those to bear in this, the first of the well-known dictionaries used in Dublin, called An Irish-English Dictionary (Dublin, 1817): "brannumh, s.m. chessmen fithchioll, chessboard." 1825 R. A. Armstrong, A Gaelic Dictionary (London, 1825): "Fitchil, Tables, a chess board." 1849 Thomas De Vere Coneys, Foclóir gaoidhilge-sacs-bearla (Dublin, 1849): "Fithchioll, chille, chiolla, s.f. a chess-board, chess, also a complete set of armour, consisting of corslet, helmet, shield, buckler, and boots." 1855 Daniel Foley, An English-Irish Dictionary (Dublin, 1855): "Chess, s. táibhleis, branamh, táiplis." 1861 Of course this list would never be complete without the authoritative voice of O'Donovan's great friend, Eugene O'Curry, a giant of Irish scholarship from Co. Clare. He translated ficheall in his famous Lectures on The Manuscript Materials of Ancient Irish History (Dublin, 1861), p.565: fithchealla, chess-playing. 1864 John O'Donovan added a supplement to a later edition of O'Reilly's dictionary, standing over his forthright statements made in the Book of Rights (27): "Brandabh, chess-men; Schacchia; Ogygia. p.311. "Oenach n-uirc tréith .i. biadh agas etach Loghmhar, clumh agas cuilcte, cuirm agas carna, brandubh agas fithcell, eich agas carbaid, milcoin agas esrecta ol chena". Cormac's Glossary in voce Orctreith. Fithcheall, fithchioll, tabula lusoriae. Ogygia, p.311; a chessboard. In Cormac's Glossary the fithchell is described as quadrangular, having straight spots of black and white, and is chimerically compared to the Church. (28) Fear fithchille, fear fidhchilli, a chessman." (29) For those who don't know, John O'Donovan was surely the most knowledgable Irish scholar in the 19th century and possibly ever. He must have travelled across most of the parishes of Ireland, in his work for the Ordnance Survey, and later he examined Irish texts from the whole history of the Irish language, when he translated the monumental Annals of the Four Masters. This gave him great width, across the different Irish dialects, and depth, deep into old Irish, in his knowledge of the language. It is therefore very significant that he was always adamant that fidchell meant chess, as he remarks here in rebuking John O'Brien (who, as we have seen, in fact did have fidhchell as chess but also gave another meaning): "Two rings and two chess-boards" - 1880 Arthur W.-K. Miller, when he translated O'Clery's Glossary in Revue Celtique vol 4 1879-1880: Beartrach .i. fithchcall no ciar imirthe, 'chessboard'. 1904 T O'Neill-Lane, English-Irish Dictionary (Dublin, 1904): "Chess, brannamh, -ainmh, m.=brann-dubh, -duibh, m.;... Chess-board, s., fithcheall, -cille, -a, f." 1904 Fr Patrick S. Dineen's work, A Concise English-Irish Dictionary (Dublin, 1904), is the definitive dictionary that came out of the Irish Ireland movement of the turn of the century, based not only on Dineen's scholarship but also with inputs from Gaelic League stalwarts like David Comyn etc etc: "Brannamh, -aimh, m., chess, a chess board, a backgammon table; the game of chess, the chess-men, the points or squares on the chess table. Fithcheall, -chille, -chealla, f. (also g. -chill, pl. -chealla, m.), a chessboard; a game of chess; clár fithchille, a chess-board; fear fithchille, a chess-man; foireann fithchille, a set of chess-men." It seems therefore as proven as any word can be that fidhchell, and brannaimh, have an unbroken line as meaning chess in the Irish language. But there is another piece of evidence, that comes this time from archaeology, which may serve to prove our case. Lewis Chess Set Probably everybody has heard of the Lewis chess pieces, which are said to have been found in c.1831 on the Isle of Lewis off the coast of Scotland. One of the first academics to write about the pieces, Frederick Madden, speculated that they may have come from Scandinavia. He was only surmising but because of this they have become classified as examples of Scandinavian art, on very thin evidence I would suggest. They are among the most famous archaeological finds in Europe, so without more ado I will just point out the Irish connections to this set. There are I believe a number of reasons to link the Lewis chess set to Ireland rather than to Scandinavia: 1. In c.1817 a number of chess pieces were discovered in a bog at Clonard in Co. Meath. Unfortunately it appears that only a king from the set survives in Ireland. It came into the possession of a Dr Tuke (31) who had a small private museum in Dublin, later Petrie owned it, then it went from there into the collections of the Royal Irish Academy which are now housed in the National Museum in Dublin. As you can see from the accompanying illustrations, the piece is exactly the same style as the Lewis ones. They must be from either the same set or at least it was the same people who used those sets? Since it was found in Clonard, a great centre of course of Irish monastic tradition and learning, not at all a centre of Viking or Scandinavian influence, it really puts the Lewis chessmen clearly into the orbit of Celtic Ireland. (32) 2. The obvious Celtic/Irish art on the Lewis chess pieces, as you can see in the photograph. 3. The Irish cultural connection to the Isle of Lewis which I respectively submit is greater than that of Scandinavia. After all when the islanders speak Gaelic, drink whiskey, and play the bagpipes they are displaying that Irish connection - whether they admit it or not! Here is just a few words on Lewis from wikipedia: "As a result of the Gaelic influence, the Lewis accent is frequently considered to sound more Irish or Welsh than stereotypically Scottish in some quarters. The Gaelic culture in the Western Isles is more prominent than in any other part of Scotland. Gaelic is still the language of choice amongst many islanders and around 60% of islanders speak Gaelic, whilst 70% of the resident population have some knowledge of Gaelic (including reading, writing, speaking or a combination of the three). Most signposts on the islands are written in both English and Gàidhlig and much day-to-day business is carried out in the Gaelic language." (33) 4. There is also two slightly mysterious aspects of the Lewis chessmen which might be explained easier in an Irish context. First of all why do you have, all together like this, multiple, seemingly new, complete chess sets to be placed it seems in one bag (because included in the find was one ornamented ivory buckle which no doubt was intended as the clasp of the bag for the chess pieces)? Presumably you only need one set to play with? Well if you look at the 'Book of Rights', that corpus of ancient rights of Irish kings, you can easily speculate why a number of new sets could be together like this. Here is an extract from it: "Entitled is the king of hospitable Conmaicne It would neatly explain this then if the Lewis chess sets could be considered one of these legal donations to the Irish kings? 5. The other mystery attached to the Lewis set is that fourteen discs were found with them. These ivory discs are clearly too big to be backgammon or draughts pieces, the resulting board would be huge, but I think it could be more easily explained. Bear in mind that there are approx. four nearly complete sets in the Lewis find and since 14 cannot be divided by 4 my guess is that there is two discs missing, giving you four discs for each set. I respectively submit that the obvious use for these discs is that they are placed at the corners of a fabric or skin chess board (note no board was found with the pieces, which would be likely if it was made of a fragile fabric that would have deteriorated quicker than the ivory pieces), to hold down the corners and also to act as candle holders to give the all important visibility for the serious chess player. This of course is the only way that the whole set could be transported around in a bag, a convenient arrangement that is copied for that reason to this day in chess tournaments. In any case what links that to Ireland is this mysterious reference from the Tain Bo Fraich: "Medb and Aillil play fidchell. Froech then begins to play fidchell with one of his men. The fidchell was lovely. A board of tinned bronze with four corners (lit. ears and elbows) of gold. A candle (made) of a precious stone shining for them. The men on the board were of gold and silver." (35)Admittedly that is somewhat ambiguous but maybe the poet meant to link the idea of candles and the four corners, and also the illusion to ears and elbows would look quite apt for a chessboard with these discs sticking out at the corners (and the illusion makes no sense otherwise). Hence it may be that this reference is to the same style of chess set as the Lewis ones. 6. A lot of people have commented on the very amusing expressions on the faces of the pieces, which is highly unusual in the context of most art in Europe at that time. Except in Ireland, if you look at the faces in the Book of Kells, for example, you will see the same slightly comical use of facial expressions. Bear in mind too that against these very strong links to Ireland, the only link to Scandinavia, as far as I know, consists of one diagram of a lost fragment of a chess piece, which looks only vaguely like the Lewis set, found in Trondheim in Norway in the 19th century. (36) This Scandinavian connection looks like complete conjecture otherwise and I would suggest that John O'Donovan was quite right to question it when he wrote: From the exact similarity, as well in style as in material, of the original, to those found in the Isle of Lewis, and which have been so learnedly illustrated by Sir Frederick Madden, in an Essay published in volume xxiv. of the Archaeologia, the Editor is disposed to believe that the latter may be Irish also, and not Scandinavian, as that eminent antiquary supposed. It would, at all events, seem certain that the Lewis chess-men and Dr. Petrie's are contemporaneous, and belonged to the same people; and no Scandinavian specimens, as far as the Editor knows, have been as yet found, or at least published, which present anything like such a striking identity in character. (37) The significance of all this then is that the Lewis set consists of bishops, kings, queens, knights, pawns, and rook-like pieces (they call them warders) which means that whoever was playing that set was certainly playing what we know now as chess. Therefore if it can be said that this set is to be identified with all those old Irish references to fidhchell and brannaimh then we have proved our case! And if you consider it carefully, why would the world and his grandmother chase off to India and Persia to explain a set found in a region with all these old references to chess? Surely the simplest thing is to recognise that these are the kind of sets that the Book of Rights etc are talking about? It goes without saying that on other hand the cultural links between Lewis and 12th century Iran and Northern India are not unduly abundant! Conclusion So to conclude I would suggest that the date of the arrival of chess in the Western Isles of Europe (e.g. Ireland, Iceland and Lewis) should be put back much further than the current theory. After all it is usually classified as somewhat a mystery as to how chess came to this part of Europe and that kind of outcome from copious historical research often means that they are underestimating how old it is. I think Ireland is a perfectly good candidate for spreading this game around these Isles, much like it spread literacy, handwriting, Latin, Christianity and art across into those parts after the fall of the Romans. Also the oldest references to chess are certainly contained in the Irish literature and anyway the Irish are, I believe, the only race who anciently claimed to have invented it (in the reign of Lugh, one of the early kings of the Tuatha de Danann). (38) As regards the Eastern game I think chess should be classified as one of those areas where a mysterious Eastern influence (doubtless because some of the races like the Tuatha de Danann would have originated in the East) can be seen in Irish culture, like Sean Nós singing (39), the harp (40), the origins of Indo-European languages (as that title suggests and of which Irish is one and of course the oldest language in this part of Europe), and even old Irish brooch designs. (41) Hence, just like in those areas, you will get two branches developing off a very old Middle Eastern root, a Western style of chess first developed and popularised by the Irish and an Eastern one which maybe spread across Persia and Northern India to China. Maybe the use of elephants in the Eastern style of chess could be a way to distinguish the two versions of the game (which in their rules probably were always very alike). That it was that this western style that evolved into the modern one can be seen for example in the use of the word 'rook', which is from the Icelandic word for a 'rook', another country within the orbit of the Irish peregrinations of the first millennium. Q.E.D.! by Brian Nugent Footnotes 1. R A Stewart Macalister, Lebor Gabála Érenn, vol 1 (Dublin, pre 1940), p.173. 2. Ed. O'Keefe, Eriu, v, p.32. 3. Ed. Myles Dillon, Serlige Con Chulaind (Dublin, 1942), 11. 405-6. 4. Amra Columcille, Revue Celtique xx, p. 283. Other descriptions of boards will be found in Tochmarc Etaine, Eriu xii, p; 174, #2; K. Meyer, Fianaigecht, p. 14, ii. 29-36. 5. Eleanor Knott, The Bardic Poems of Tadhg Dall Ó Huiginn (London, 1926), vol 2 p.198-199. 6. http://www.ucd.ie/tlh/text/ws.tig.001.text.html . This is the version as published in 1868: "Fidchell [Fithcill B (i)] i. féth-ciall, fáth-ciall i.e. it requires sense (ciall) and fáth ('learning') in playing it. Or fuath-cell, i.fuath cille 'likeness of a church', in the first place, the fidchell is four-cornered, its squares are right-angled, and black and white are on it, and, moreover, it is different people that in turn (ii) win the game. Sic et ecclesia per singula per iiii. terrae partes iiii. evangeliis pasta (iii). It is straight in the morals and points of the Scripture (iv) et nigri [i. dub B] et albi [i. gel B] i.e. boni et mali, habitant in ecclesia.(v)" Footnotes i. B is the Yellow Book of Lecan, TCD MS 1318 (H.2.16), otherwise the text is from RIA Ms 1230 (23 P 16), pp. 263-72. ii. cach la fecht, cf. cach la céin (gl. modo) Z. 1017, 1018.- Whitley Stokes. iii. B glosses this by: is marsin a neclais ic sassud cethri rann sundradach in betha o soscelaib "So is it in the Church, satisfying the four different parts of the world with gospels.", which is not accurate. - Whitley Stokes. iv. "The Scriptures are straight in their morals (doctrines) and points".- John O'Donovan. v. fidchell = W[elsh] gwyddbwyll - Whitley Stokes." (trans. by John O'Donovan, edit. by Whitley Stokes, Cormac's Glossary (Calcutta, 1868), p.75-76.) 7. Eoin Mac White in Éigse vol 5 1945, p.22-35, available at: http://www.unicorngarden.com/eigse/eigse01.htm . Note the comparison to the old morality tales based on chess, which maybe this is an early example of? It reads very like the 'Morality of Chess' attributed to Pope Innocent III c.1210: "This whole world is nearly like a chess-board, of which the points are alternately white and black, figuring the double state of life and death, grace and sin. The families of this chess-board are like the men of this world..." ( http://www.worldchesslinks.net/ezif07.html .) 8. See the P W Joyce entry in the Appendix. 9. See the end of the O'Donovan entry in the Appendix. 10. See under H J Lloyd in the Appendix. 11. I include fidhchell and brannaimh as the same game (unlike Eoin Mac White and P W Joyce) in this article because I think most of the available entries use them interchangeably like this, as you can see for example in the dictionary entries listed infra. It seems that some entries explicitly state that the two games are different (see e.g. under Joyce in the Appendix), and some entries are pretty explicit in saying they are the same (for this see under Knott in the Appendix), and in any case it is unlikely to be that fidhchell is the chess like game and brannaimh not (as Mac White and Joyce make it) because Keating uses brannaimh to explicitly denote chess. No doubt over the whole course of the use of chess in Irish history its probable that some variation of chess was meant at times for these words, or indeed across different parts of Ireland, but in general I think brannaimh and fidhchell are just two words with the same meaning, which is very often the case in Irish vocabulary. Incidentally there is no doubt at all that brandubh is not a different game to brannaimh, unlike what Mac White says, for example Robert Atkinson, in his edition of Keating's 'Three Shafts.." notes this in the index under bran-dubh:"now generally written brannaimh". And when Osburn Bergin updated that text he just dropped the 'bran-dubh' completely, calling all such references brannaimh. (Rev Geoffrey Keating, edit by Robert Atkinson, The Three Shafts of Death (Dublin, 1890), p.320.) 12. See for example under Duncan Forbes in the Appendix. 13. See under Walker in the Appendix. 14. See under Joyce ibid. 15. Eoin Mac White, Early Irish Board games, in Éigse vol 5 1945, p.22-35, footnote 43, available at: http://www.unicorngarden.com/eigse/eigse01.htm . 16. Btw the etymology of fidhchell - the important, unchangeable part, of the word is the beginning which is pronounced fil - is quite interesting because probably, as Vallancey first pointed out, it is related to the old name for one of the pieces in chess, as you can see in this quote from 1841: "THE BISHOP. Among the Persians and Arabs, the original name of this piece was Pil, or Phil, an elephant; under which form it was represented on the eastern chess-board. It appears that the Spaniards borrowed the term from the Moors, and with the addition of the article al, converted it into alfil, whence it became varied by Italian, French, and English writers into arfil, alferez, alphilus, alfino, alphino, alfiere, aufin, alfyn, awfyn, and alphyn. ... The French, at a very early period, called this piece Fol, an evident corruption of Fil. Hence, also, the French name for the piece Fou, or the fool, a natural perversion of the original, when we consider that, at the time it was made, the court fool was a usual attendant on the King and Queen: or, as Mr. Barrington observes, "This piece, standing on the sides of the king and queen, some wag of the times, from this circumstance, styled it The Fool, because anciently royal personages were commonly thus attended, from want of other means of amusing themselves." (The Saturday Magazine 27th February 1841 available at: http://www.worldchesslinks.net/ezif05.html .) 17. Whitley Stokes, The Second Battle of Moytura in Revue Celtique (Paris, 1891) vol 12, p.79, Mss source British Library, Harleian Ms 5280, 63a-70b dated to c.1512 as you can see on the UCC site: http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/G301025/header.html . 18.Eoin Mac White op. cit. 19. Fr Geoffrey Keating, edit by Robert Atkinson, The Three Shafts of Death (Dublin, 1890), p.25, this text from the updated edition: Osburn Bergin, The Three Shafts of Death (Dublin, 1931), p.30-31. 20. Eoin Mac White in his article on Irish board games in Éigse vol 5 1945, p.29, available at: http://www.unicorngarden.com/eigse/eigse01.htm . 21. As you can see in: Fr Geoffrey Keating, Foras Feas ar Éireann (London, 1908) vol III, p.312. 22. Another translation of the will of Cathair Mór who was crowned in 174: "I also bequeath ten four-horsed chariots, five chess-boards, with five sets of chess-men; 30 shields, with gold and silver bosses, and 50 sharp-edged swords, to Tuathal Tigeach the son of Maineamail. ... I also bequeath to Crimthandan, 15 polished chess-boards, with 20 sets of choice speckled chess-men, and the supremacy of the province of Leinster." (by P.T.O, Analysis of the Book of Lecan (between folio 184-191) in the Christian Examiner and Church of Ireland Magazine (Dublin, 1832) Vol 1, p.779-780.) 23. Charles Vallancey, An Account of the Ancient Stone Amphitheatre... (Dublin, 1812), p.32. 24. Charles Vallancey, A Grammar of the Hiberno-Celtic or Irish Language (Dublin, 1782), p.85, translating from the Latin of Dr Thomas Hyde, Mandragorias, seu, Historia shahiludii (Oxford, 1694). 25. Fr John O'Brien, Catholic Bishop of Cloyne, Focalóir Gaoidhilge-Sacs-Bhéarla or an Irish-English Dictionary (1st ed. Paris, 1768, 2nd edition edited by Bishop Robert Daly, C of I Bishop of Cashel, in Dublin, 1832. Incidentally Fr O'Brien stated that he particularly followed Edward Lhuyd in Archaeologia Britannica (1707), although he certainly changed the chess entries because Lhuyd went with: "Branuimh, Coats of Mail K[eating, derived from]. Fithchille, A Pair of Tables. K[eating]. Fithchioll: Eadach fitchioll, A coat of mail. K[eating]." 26. Charlotte Brooke, Reliques of Irish Poetry (Dublin, 1789), p.95. 27. John O'Donovan and Edward O'Reilly, An Irish-English Dictionary (Dublin, 1864). 28. The Dictionary entry continues: "Sic et ecclesias per singulas quatuor terrae partes quatuor Evangeliis pasta: is dírech a mbésaibh ocus hi tithibh na screaptra et nigri et albi, i.e. boni et mali habitant in ecclesia". "Fithchiall .i. a clár imeartha", a playing board. O'Clery Ms. The following description of the fithchell will throw additional light upon its form; it is taken from Leabhar na h'Uidhri, a Ms of the twelfth century. "Cia t'ainmseo, ol Eochaidh, Ní ardairc son, ól se, Midir bregh léth. Cid dot roacht? ol Eochaid. Do imbirt fidchille frit-su, ol se. Am maith-se ém, ol Eochaidh for fithchill? A fromud dún, ol Midir. Atá, ol Eochaidh, ind rigan i na cotludh, is lé in teach a tá ind fithchell. Ata sund chenae, ol Midir, fidhchill nad messo. Ba fír ón: clár nargit ocus fir óir, ocus fursunad cacha hairdi fors in clár di liic logmair, ocus fer bolg di figi rond credumae. Ecruid Midir in fidhchill, iar sin. Imbir, ol midir. Ní immér acht di giull, ol Eochaid. Cid gell bias and? ol Midir. Cumma lim, ol Eochaíd. Rot bia limsa, ol Midir ma tu bereas mo thochell caegat gabur ndub-glas, etc." Tochmair n-Etainec. "Ba and bhoi Cuchullainn oc imbirt fidhchille ocus Loeg mac Riangabhra a aura féisin. Is dom chuithbhiudhsa ón, or sé, do bherta bréc im nach mearaighe. Lasodain dolléci dia fearaibh fidhchilli don techtaire co m-boi for lár a inchinne." Tain bo Cuailgne, as in Leabhar na h'Uidhri. See fear fithchille. 29. More from the dictionary entry: "Ciar bo mór ocus ciar bo aireaghdha trá Loeghaire tallastar in oen glaic ind fir dod fainc feib talladh mac bliadhna ocus cot nomalt etir a bhi bhois iarsudiu amail tairidnider fear-fidhcilli for tairidin". Leabhar na h-Uidhri." 30. John O'Donovan, Book of Rights (Dublin, 1847), p. 70-71. 31. Dr Edward Francis Tuke (c.1778-1846), a Quaker from a family originally said to be from Bristol, was the owner of a private antiquarian museum (visited by Walter Scott in 1825) at 106 Stephen's Green West in Dublin. Later (c.1837) he founded Manor Farm House, Chiswick, London, as a private mental asylum. He died on the 25th May 1846. His son was Dr Thomas Harrington Tuke (1826-1888), and grandsons Dr Thomas Seymour Tuke (c.1856-1917) and Dr Charles Molesworth Tuke (1857-1925), the last three being all psychiatrists who continued to run the asylum in Chiswick. These are not the same as the Hack Tukes from Yorkshire. His father was doubtless the Thomas Tuke M.D. who died in Stephen's Green Dublin on the 20th of February 1820. 32. That it was found at Clonard you can see here: http://homepage.tinet.ie/~clonardns/thechesspiece.htm , where you can also see a photograph of it. See also the piece by John O'Donovan in the Appendix infra. 33. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis . 34. John O'Donovan, Book of Rights (Dublin, 1847), p.115. 35. Ed. M. Byrne and Myles Dillon, Tain Bo Fraich, ll. 88-93. 36. Christopher McLees and Oystein Ekroll, Notes and News: A Drawing of a Medieval Ivory Chess Piece in Medieval Archaeology, 1990 no.32, p.151-154, available at: http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/arch-769-1/ahds...4.pdf . 37. See under John O'Donovan in the Appendix. 38. "Lag s. Cian s. Dian Cecht s. Esarg s. Net s. Indui s. Alldui, he is the first who brought chess-play and ball-play and horseracing and assembling into Ireland, unde quidam cecinit." (R A Stewart Macalister, Lebor Gabála Érenn (Dublin, 1941), vol 4, p.129). 39. "To the first-time listener, accustomed to pop and classical singers, sean-nós often sounds more "Arabic" or "Indian" than "Western"" ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sean-n%C3%B3s_song ). 40. See for example at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harp . 41. As can be seen in the acompanying photograph of an Algerian lady wearing what looks like the Irish style of brooch (from J Romilly Allen, Celtic Art in Pagan and Christian Times (London, 1904), p. 224). APPENDIX Some extracts from articles or notes on Irish chess which might serve as a brief historiography of this question. Apologies for the repetition of some points. Charles Vallancey (1782) "The Arabian name of this piece is als Phil, and means the elephant; from whence Alphillus used by the old Latin poets: The French call this man fol. I have not been able to find the Irish names of the men of this game, but it was universally played by the ancient nobility of Ireland. ... Schah is King in Persian, and Schah mat, the King is dead; in Irish Seath mutha, which is converted into Check mate in English. The Chinese call this game Phil, i.e. the elephant, which is the same name as given it by the Irish, Phill or Fithill. Cabura is another Indian name of a man at this game, signifying a pledge or hostage, in Irish Cathurra." (Charles Vallancey, A Grammar of the Hiberno-Celtic or Irish Language (Dublin, 1782), p.84-85.) Joseph Cooper Walker (1790) "In the old Brehon Laws we find, that one tax, levied by the Monarch of Ireland on every province, was to be paid in Chess-boards and complete sets of men: and that every Bruigh (or Inn holder of the states) was obliged to furnish travellers with salt provisions, lodging, and a Chess-board gratis. ... In a description of Tamer-Hall [Tara] during the Pagan Ages, lately discovered in the Seabright collection, Fidhcheallaigh, or Chess-players, appear amongst the officers of the household. And in the Liber Lecanus, the oldest Irish manuscript extant, we are told that Cathir the Great, who reigned in the second century, bequeathed Chess-boards and sets of men to his son and nobles. Nor has the game of Chess escaped the notice of the Irish romance writers of the middle ages; we often find their heroes engaged in this "mimic-war". In a celebrated metrical romance called Laoi na Seilge, now lying before me, the author numbers Chess with the amusements of his hero Fin Mac Cumhal. ... How long chess continued a prevailing game in Ireland I cannot learn: engaged during many centuries, with feats of arms, History seldom condescended to enquire into the private life of the persecuted Irish. ... But chess was not the only game on the tables in use among the early Irish: the game of Falmer sometimes beguiled the leisure of our ancestors. Three persons were concerned in this game, and each throw the dice by turns. And it has been observed, that the rustics in Connaught play at Taibh-liosg, or Backgammon, remarkably well at this day. "It is no uncommon sight (says Col. Vallancey) to see tables cut out of a green sod, or on the surface of a dry bog." (1) The dice are made of wood or bone. I have observed elsewhere, that Carolan, when blind, continued to play at Backgammon with eminent skill. (2)" Footnotes 1. Collect. de Reb. Hib. vol 3, p.530. 2, Hist. Mem. of Irish Bards, Append. p.68. (Joseph Cooper Walker (1761-1810), Anecdotes on Chess in Ireland, in Charles Vallancey, Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicis (Dublin, 1790) vol 5, pp.366-68.) John O'Donovan (1847) "Of Chess among the ancient Irish. The frequent mention of chess in this work [Book of Rights] shows that chess-playing was one of the favourite amusements of the Irish chieftains. The word fithcheal is translated "tabulaea lusoriae," by O'Flaherty, where he notices the bequests of Cathaeir Mor, monarch of Ireland, Ogygia, p. 311. In Cormac's Glossary, the fithcheal is described as quadrangular, having straight spots of black and white. It is referred to in the oldest Irish stories and historical tales extant, as in the very old one called Tochmarc Etaine, preserved in Leabhar na h-Uidhri, a Manuscript of the twelfth century, in which the fithchell is thus referred to: ... "'What is thy name?' said Eochaidh. 'It is not illustrious,' replied the other, 'Midir of Brigh Leith.' 'What brought thee hither?' said Eochaidh. 'To play fithcheall with thee,' replied he. 'Art thou good at fithcheall?' said Eochaidh. 'Let us have the proof of it,' replied Midir. 'The Queen,' said Eochaidh, 'is asleep, and the house in which the fithcheall is belongs to her.' 'There is here,' said Midir, 'a no worse fithcheall.' This was true, indeed: it was a board of silver and pure gold, and every angle was illuminated with precious stones, and a man-bag of woven brass wire. Midir then arranges the fithcheall. 'Play,' said Midir. 'I will not, except for a wager,' said Eochaidh. 'What wager shall we stake?' said Midir. 'I care not what,' said Eochaidh. 'I shall have for thee,' said Midir, 'fifty dark grey steeds, if thou win the game.'" The Editor [O'Donovan] takes this opportunity of presenting to the reader four different views of the same piece, an ancient chess-man—a king—found in Ireland, which is preserved in the cabinet of his friend, George Petrie, LL.D. ; he has never discovered in the Irish MSS. any full or detailed description of a chess-board and its furniture, and he is (1), therefore, unable to prove that pieces of different forms and powers, similar to those among other nations, were used by the Irish, but he is of opinion that they were. From the exact similarity, as well in style as in material, of the original, to those found in the Isle of Lewis, and which have been so learnedly illustrated by Sir Frederick Madden, in an Essay published in volume xxiv. of the Archaeologia, the Editor is disposed to believe that the latter may be Irish also, and not Scandinavian, as that eminent antiquary supposed. It would, at all events, seem certain that the Lewis chess-men and Dr. Petrie's are contemporaneous, and belonged to the same people; and no Scandinavian specimens, as far as the Editor knows, have been as yet found, or at least published, which present anything like such a striking identity in character. Dr. Petrie's specimen was given to him about thirty years ago by the late Dr. Tuke, a well-known collector of antiquities and other curiosities in Dublin; and, as that gentleman stated, was found with several others, some years previously, in a bog in the county of Meath. The fear fithchille, or chessman, is also frequently referred to in old tales, as in the very ancient one called Tain bo Cuailghne, in which the champion Cuchullainn is represented as killing a messenger, who had told him a lie, with a fear fithchille: ... "Cuchullainn and his own charioteer, Loegh, son of Riangabhra, were then playing chess. 'It was to mock me,' said he, ' thou hast told a lie about what thou mistakest not.' With that he cast [one] of his chessmen at the messenger, so that it pierced to the centre of his brain." —Leabhar na h-Uidri. Again, in a romantic tale in the same MS., the Fear fithchilli is thus referred to: ... "Though great and illustrious was Loeghaire, he fitted on the palm of one hand of the man who had arrived as would a one-year old boy, and he rubbed him between his two palms, as the fear fithchille is drawn in a tairidin." See also Battle of Magh Rath pp. 36, 37." ... The Fitcheall is described in Cormac's Glossary as quadrangular with straight spots of black and white, is cethrachair in fithchell, ocus it dirge a títhe, ocus find ocus dubh fuirre. Footnotes 1. See the line in p. 242, fóirne co n-a bh-fhichthillaibh, MS. L. - the family, brigade, or set of chessmen, - foirne finna is the reading in MS. B. In another place, page 246, we have fichthill acus brandubh bán, a chessboard and white chessmen; which words may be considered to determine the color, white. The chess king in Dr. Petrie's cabinet is of bone, of very close texture, and is the same size as the above engraving." (John O'Donovan, Book of Rights (Dublin, 1847), p.lxi-lxi, 35.) Standish Hayes O'Grady (1855) "Chess was the favourite game of the Irish in the most ancient times of which we have any account, as appears from the constant mention of it in almost all romantic tales.... "After they had made this speech Fionn asked for a chessboard to play, and he said to Oisin, "I would play a game with thee upon this [chess-board]." They sit down at either side of the board; namely, Oisin, and Oscar, and the son of Lughaidh, and Diorruing the son of Dobhar O'Baoisgne on one side, and Fionn upon the other side. Howbeit they were playing that [game of] chess with skill and exceeding cunning, and Fionn so played the game against Oisin that he had but one move alone [to make], and what Fionn said was: "One move there is to win thee the game, Oisin, and I dare all that are by thee to shew thee that move." Then said Diarmuid in the hearing of Grainne: "I grieve that thou art thus in a strait about a move, Oisin, and that I am not there to teach thee that move." It is worse for thee that thou art thyself," said Grainne, "in the bed of the Searbhan Lochlannach, in the top of the quicken, with the seven battalions of the standing Fenians round about thee intent upon thy destruction, than that Oisin should lack that move." Then Diarmuid plucked one of the berries, and aimed at the man that should be moved; and Oisin moved that man and turned the game against Fionn in like manner. It was not long before the game was in the same state the second time, [i.e. they began to play again, and Oisin was again worsted], and when Diarmuid beheld that, he struck the second berry upon the man that should be moved; and Oisin moved that man and turned the game against Fionn in like manner. Fionn was carrying the game against Oisin the third time, and Diarmuid struck the third berry upon the man that would give Oisin the game, and the Fenians raised a mighty shout at that game. Fionn spoke, and what he said was: "I marvel not at thy winning that game, Oisin, seeing that Oscar is doing his best for thee, and that thou hast [with thee] the zeal of Diorruing, and the skilled knowledge of the son of Lughaidh, and the prompting of the son of O'Duibhne."" (Standish Hayes O'Grady, Transactions of the Ossianic Society for the year 1855 (Dublin, 1857) vol 111, p.144-147.) John O'Daly (1856) "This was the favourite game of the ancient Irish chieftains; and is frequently referred to in the earliest manuscripts extant.... (John O'Daly, Transactions of the Ossianic Society for the year 1856 (Dublin, 1859) vol 4, p.56-57.) Duncan Forbes (1860) "Chess among the Irish That the Irish may have received the game of Chess from the Danes and Norwegians in the tenth or eleventh century is quite possible; but it is much more likely that it was introduced among them by the Anglo Normans in the twelfth or following century. To pretend, as their chroniclers do, that they were acquainted with the game in the first century of the Christian era is simply absurd. As the subject, however, is very curious, to say the least of it, I here lay before the reader a few extracts to that effect from highly reputable Irish writers, to which I append a few notes and comments of my own. ...[the chess king described by O'Donovan] bears no small resemblance to some of the Lewis chessmen in the British Museum...At the same time I cannot help thinking that Mr O'Donovan's inference is a little Irish, to say the least of it - viz. , that "the Lewis Chessmen are Irish also, and not Scandinavian, as Sir Frederic supposed." He overlooks the serious fact, that the presence of one stray swallow does not constitute a summer; and even if the whole set of chessmen to which this solitary king belonged, had been discovered, it would have proved that these had been carved in Ireland. It is, however, quite needless for us to enter into any argument on this subject till it is satisfactorily shewn that the Irish word "Fithcheall" really denoted the game of Chess. ... As the case stands then, with regard to Irish Chess, we may safely say with Sir Frederic Madden that, "the fact is not proven;" and we may further state, though it may sound somewhat paradoxical, that even if the fact were proven, the more improbable would it become. It would simply lead into an inextricable dilemma, viz., either that the ancient Irish invented the game of Chess independent of the Hindus; or that in ancient times, say two or three thousand years ago, the Irish must have had intercourse with India. Both of these suppositions are utterly inadmissable. The probability that two individuals should, independent of one another, have each invented so scientific and complex a game as Chess, is certainly not above one to a hundred millions. Again, the supposition that the ancient Irish knew anything of India or of the Hindus, who did invent the game, is equally absurd and extravagant." (Duncan Forbes, The History of Chess (London, 1860), p.xl-xlvi.) Whitley Stokes (1862) "A word which would speak highly for the civilization of the Irish, if its usual interpretation were certainly correct, is fidchell, gen. fidchille, p. 21, commonly rendered 'chess'. Various passages from Irish MSS. bearing on this subject have been noticed by Dr. O'Donovan in his "Book of Rights," Pref. p. XIV, and the fidchell is mentioned in the text and comment of some Brehon laws preserved in H. 3, 17, cols. 402 d, 406. The following seem the only facts as yet established regarding fidchell: 1. That the word is etymologically identical with the Welsh gwyddbwyll (= gwydd + pwyll*), the Irish c corresponding as usual with the Welsh p. 2. That it was played on a quadrangular board divided into rectilinear spaces. 3. That some of the pieces were white and the rest were black. 4. That they were called fir fidchille, men of fidchell, or foirenn (= W. gwerin), were kept when not in use in a man-bag (fer-bolg), and were occasionally large enough to serve as the murderous missiles of infuriated players. All this is consistent with holding that the game was merely a kind of draughts, something like one or other of the games comprised under the term [greek text]. I propose to derive fidchell from fid (='wood', W. gwydd, Gaulish vidu) and cell = W. pell f. 'a pell-et', [Greek word]. The weak point about this etymology is the necessity of assuming an Irish cell, which, with the required meaning, is not producible. * Gwydd-bwyll no doubt should be in Irish fid-chíall. But in the latter language the word is always fid-chéll or fid-chíll. This, then, leads one to think that the Welsh may have altered gwydd-bell into gwydd-bwyll to suit a fancied derivation from gwydd 'wood', 'board', and pwyll (= cíall), 'sense', 'reason', just as they have changed cubiculum into cuddigl, from a supposed connection with their verb cuddio 'to hide'. The spelling fithchell is wrong." (Whitley Stokes, Three Irish Glossaries (London, 1862), p.liii-liv, xxxvii-xxviii.) Henry Edward Bird (1893) "The word, chess, whatever it may have signified, was common in Ireland long before it is ever found in English annals. The quotation from the Saxon Chronicle, of the Earl of Devonshire and his daughter playing chess together, refers to the reign of Edgar, about half a century before Canute played chess; but in Ireland the numerous references and legacies of chess-boards are of eight hundred years' earlier date. Several scholars in Ireland have discussed the question of probable early knowledge of chess there. Fitchell, a very ancient game in that country, was uniformly translated, chess. O'Flanagan, Professor of the Irish language in the University of Dublin, writing to Twiss about the end of last century in reference to Dr. [Thomas] Hyde's quotations, thought Fitchell meant chess. J. C. Walker wrote:--"Chess is not now (1790) a common game in Ireland; it is played at and understood by very few; yet it was a favourite game among the early Irish, and the amusement of the chiefs in their camps. It is called Fill, and sometimes Fitchell, to distinguish it from Fall, another game on the Tables, which are called Taibhle Fill. The origin of Fill in Ireland eludes the grasp of history." The Chess King preserved by Dr. Petrie, L.L.D., bears no small resemblance to those found in the Isle of Lewis, now in the British Museum, and which have been graphically reported upon by Sir F. Madden. John O'Donovan, Esq., author of our best Irish Grammar, in "Leabhar na'q Ceart, or the Book of Rights," 1847, from MS. of 1390 to 1418, frequently refers to the game, and the legacies of Cathaeir Mor, who reigned 118 to 148, contain, among other remarkable bequests, thirteen of chess-boards. Once a set of chess-men is specified--and, again, a chess-board and white chess-men. The bequests of the said Cathaeir Mor are also cited by O'Flaherty, who mentions to have seen the testament in writing, and in Patrick O'Kelly's work, Dublin, 1844, "The History of Ireland, Ancient and Modern," taken from the most authentic records, and dedicated to the Irish Brigade, translated from the French of Abbe McGeoghegan (a work of rather more than a century ago). Col. Vallancey, in his "Collectanea de Reb. Hib.," seems to insinuate that the Irish derived it with other arts from the East. "Phil," says he, "is the Arabic name of chess, from Phil, the Elephant, one of the principle figures on the table." In the old Breton [Brehon] Laws we find that one tax levied by the Monarch of Ireland in every province was to be paid in chess-boards and complete sets of men, and that every Burgh (or Inn-holder of the States) was obliged to furnish travellers with salt provisions, lodging, and a chess-board, gratis. (Note: That must have been very long ago.) In a description of Tamar or Tara Hall, formerly the residence of the Monarch of Ireland--it stood on a beautiful hill in the county of Meath during the Pagan ages--lately discovered in the Seabright Collection, Fidche-allaigh, or chess-players, appear amongst the officers of the household. "Langst ver der Erfindung," says Linde; and again, "Wenn die ganze geschicte von Irland ein solches Lug-gund Truggewebe ist, wie das Fidcill Gefasel ist sie wirklich Keltisch."" (Henry Edward Bird, Chess History and Reminiscences (London, 1893), p.181-182.) H J Lloyd (1896) "Of the antiquity of Chess in Ireland we have many proofs; but it would be a difficult subject to treat of the precise manner in which Chess may have been originally played, or what degree of resemblance the modern game bears to the ancient one. I intend merely to give some of the Irish references to Chess, and to quote the authorities for the statements I make. ... Maelmuire, Prince of Leinster, was staying at Kincora with Brian Boru, and his son Morrogh. Maelmuire, who was watching a game of chess, recommended a false move, upon which Morrogh observed it was no wonder his friends the Danes (to whom he owed his elevation) were beaten at Glenmanna, if he gave them advice like that." (H J Lloyd, The Antiquity of Chess in Ireland, in Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland vol 7 1886, p.659.) P W Joyce (1920) "Chess. In ancient Ireland chess-playing was a favourite pastime among the higher classes. Everywhere in the Romantic Tales we read of kings and chiefs amusing themselves with chess, and to be a good player was considered a necessary accomplishment of every man of high position. At banquets and all other festive gatherings this was sure to be one of the leading features of the entertainment. In every chief's house there was accordingly at least one set of chess appliances for the use of the family and guests: and chess-boards were sometimes given as part of the tribute to kings.(1) Chess furniture was indeed considered in a manner a necessity, so much so that in this respect it is classified in the Brehon Law with food.(2) As to the general form and construction of the chessboard there can be no doubt, for Cormac's Glossary (p. 75) describes it with much exactness. This old authority states first, in regard to the game, that the play demands ciall and fith [keeal, faw], i.e. attention and judgment: and it goes on to say that the fidchell or chess-board was divided into black and white compartments by straight lines: that is to say, into black and white squares. The game was called fidchell or fidchellecht [fihel, fihelleght]: and fidchell was used to designate the chess-board. But this was also called clár-fidchilli, clár being the general name for a board or table. The chessmen were called fir-fidchilli, i.e. 'men of chess,' or collectively foirenn, which is the Irish word for a party or body of men in general. The whole set of furniture was called fidchellecht (3) or fidchell. The men, when not in use, were kept in a fer-bolg or 'man-bag,' which was sometimes of brass or bronze wire woven. The chiefs took great delight in ornamenting their chessboards and men richly and elaborately with the precious metals and gems. We read in the "Story of the Battle of Mucrime," that when the Irish chief Mac Con was an exile in disguise at the court of the king of Scotland, the king's chessmen were of gold and silver: meaning ornamented with these metals.(4) The following quotation from a much older authority—the "Courtship of Etain" in the Book of the Dun Cow—is very instructive and very much to the point. Midir the fairy king of Bri-leith, comes on a visit to King Ochy :— "What brought thee hither?" said Ochy. "To play chess with thee," answered Midir. "Art thou good at chess?" said Ochy. "Let us try it," said Midir. "The queen is asleep," said Ochy, "and the house in which are the chessboard and men belongs to her." "Here I have as good a set of chess," said Midir. That was true indeed; for it was a board of silver and pure gold; and every angle was illuminated with precious stones; and the man-bag was of woven brass wire."(5) In the Will of Cahirmore, king of Ireland in the second century, we are told that he bequeathed his chessboard and chessmen to his son Olioll Ceadach (6) —an indication of their great value. The men were distinguished half and half, in some obvious way, to catch the eyes of the two players. Sometimes they were black and white. The foirenn or party of chessmen of Crimthan Nia Nair, king of Ireland about the first century of the Christian era, are thus described :— "One-half of its foirenn was yellow gold, and the other half was findruine" (white bronze).(7) Many ancient chessmen have been found in bogs, in Lewis and other parts of Scotland: but so far as I know we have only a single specimen belonging to Ireland, which was found about 1817 in a bog in Meath, and which is now in the National Museum, Dublin. It is figured here, full size. We frequently read in the tales that a hero, while playing chess, becoming infuriated by some sudden attack or insulting speech, flings his chessman at the enemy and kills or disfigures him. When we remember that chessmen were sometimes made partly of metal and were two and a half inches long, we may well believe this. The game must, sometimes at least, have been a long one. When St. Adamnan came to confer with King Finachta, he found him engaged in a game of chess: but when his arrival was announced, the king, being aware that he had come on an unpleasant mission, refused to see him till his game was finished: whereupon Adamnan said he would wait, and that he would chant fifty psalms during the interval, in which fifty there was one psalm that would deprive the king's family of the kingdom for ever. The king finished his game however; and played a second, during which fifty other psalms were chanted, one of which doomed him to shortness of life. But when he was threatened with deprivation of heaven by one of the third fifty, he yielded, and went to Adamnan.(8) That the Irish retained the tradition of the origin of chess as a mimic battle appears from the name given to the chessmen in the story of the Sick Bed of Cuculainn (p. 99) in the Book of the Dun Cow :—namely fíanfidchella, i.e. as translated by O'Curry, 'chess-warriors'; fían, a champion or warrior': from which we may infer that the men represented soldiers. Another game called brannuighecht, or 'bran-playing,' as O'Donovan renders it, is often mentioned in connexion with chess; and it was played with a brannabh, possibly something in the nature of a backgammon board. A party of Dedannans were on one occasion being entertained; and a fidchell or set of chess furniture was provided for every six of them, and a brannabh for every five, (9) showing that chess-playing and brannaimh playing were different, and were played with different sets of appliances. Among the treasures of the old King Feradach are enumerated his brandaibh and his fithchella.(10) The Brehon Law prescribes fithchellacht and brannuidhecht (as two different things) with several other accomplishments, to be taught to the sons of chiefs when in fosterage.(11) Notwithstanding that chess-playing and brannaimh playing are so clearly distinguished in the above and many other passages, modern writers very generally confound them: taking brannuighecht to be only another name for fitchellecht or chessplaying, which it is not. There is still another game called buanbaig or buanfach, mentioned in connexion with chess and brainnaimh playing, as played by kings and chiefs. When Lugaid mac Con and his companions were fugitives in Scotland, they were admired for their accomplishments, among them being their skilful playing of chess, and brandabh, and buanbaig.(12) Nothing has been discovered to show the exact nature of those two last games. I have headed this short section with the name "Chess," and have all through translated fitchell by 'chess,' in accordance with the usage of O'Donovan, O'Curry, and Petrie. Dr. Stokes, on the other hand, uniformly renders it "draughts." But, so far as I am aware, there is no internal evidence in Irish literature sufficient to determine with certainty whether the game of fitchell was chess or draughts: for the descriptions would apply equally to both. Footnotes 1. Book of Rights, 39. 2. Br Law, 1. 143, 12. 3. Book of Rights, 201, I7. 4. Silva Gad., 351 : see also Keating, 290, top ; and FM, a.d. 9. 5. See O'Donovan, in Book of Rights, Pref., lxi. 6. Book of Rights, 201. 7. Rev. Celt., xx. 283. 8. Silva Gad., 422. 9. Ibid., 250: Ir. text, 220, 50. 10. Three Fragments, 8, 12. 11. Br Laws, II 155, 9; 157, bottom. 12. O'Grady, Silva Gad., 351, top: Ir. text, 312, 30, 31: Revue Celtique xiii. 443." (P W Joyce, A Social History of Ancient Ireland (Dublin, 1920), p.477-481.) Eleanor Knott (1926) "'king,' branán is the term for a piece in the game brannumh (brandub Contribb.). It is common as an epithet for a chief: b. déd chláir na ccuradh L 17, 47b; infra 18. 16, 25. 22; b. branduibh Keat. Poems 1450. The word seems usually to denote the chief piece, but cf. a bhranáin uaisle 'his noble champions,' GF viii 15; branáin Gaoidheal druim ar druim Bk. I99a. The meaning 'chief piece,' 'king,' is supported by the following citations, which also throw a little light on the nature of the game: Imlecán mhuighe Fáil finn . ráth Temhrach, tulach aoibhinn sí ar certlár an mhuighe amuigh . mar shnuighe ar bhrecclár bhrannuimh. Gluais chuige, budh céim bisidh . ling suas ar an suidhisin [leg. snuidhisin ?] riot, a ri, as cubhaidh an clár . as tí bhunaidh do bhranán Do bhraithfinn dhuit, a dhéd bhán . saoirthíthe bhunaidh branán . . . suighter duit orra (the poet names the five capilals: Teamhair, Caiseal, Cruacha, Nás, Oileach) Branán óir guna fedhuin . tú is do chethra cóigedhuigh tú, a rígh Bhredh, ar an ttí thall . as fer ar gach tí ad tiomchall. 'The centre of the fair plain of Fál is Tara's castle, delightful hill; out in the exact centre of the plain, like a mark on a particolored brannumh board. Advance thither, it will be a profitable step; leap up on that square [lit. point, cf. the use of tí Corm. Y 607] which is proper for the branán the board is fittingly thine. I would draw to thy attention, O white of tooth, to the noble squares proper for the branán (Tara, Cashel, Croghan, Naas, Oileach), let them be occupied by thee. A golden branán with his band art thou with thy five provincials; thou, O king of Bregia, on yonder square, and a man on each square around thee.' L 17, 26 b (poem beg. Abair riom a Éire ógh, attributed to Maoil Eóin Mac Raith); Atá brainech bhruighen lán . uime mar féin na mbranán, ib. 29 b. The number of pieces in the set was apparently thirteen, see Acall. 3949-50. In a b. óir ós fidhchill, it is implied that brannumh and fidhcheall refer to the same game, but cf. Acall. pp. 218-19. Both brannumh and fidhcheall are used of the boards on which the respective games were played: as terc má do bhí ar bhrannamh bert mar í, 'scarcely has there ever been such a move on that brannumh board,' L 17, 102 b, and see above; for fidhcheall see Corm. Y 607. This rather long digression may be pardoned in view of our scanty evidence on the nature of ancient Irish games. The gloss on branán cited from 23 L 34 in the glossary to Dánfhocail is apparently by Peter O'Connell, as O'Curry states (H. & S. Cat.) that the additional notes in this MS. are in P. O'C.'s handwriting. In his dictionary P. O'C. has branán 'a pleasant agreeable witty fellow.'..and add to the exx cited the proverbial clár nocha bí gan branán Unpublished Irish Poems xxvi." (Eleanor Knott, The Bardic Poems of Tadhg Dall Ó Huiginn (London, 1926), vol 2 p.198-199, 266.) Eoin Mac White (1945) "Early Irish Board Games Owing to the meagre and vague character of the evidence, the student who would elucidate the nature of the various board games mentioned in early Irish literature must tread warily. Not only is the evidence slight and ambiguous but it is sometimes contradictory. However some possibilities and probabilities can be shown, and a few impossibilities likewise. One of the latter is the popular fallacy that fidchell and brandub were chess or draughts. Both fidchell and brandub are frequently mentioned in the saga literature of the Ulster cycle, and fidchell is mentioned in the Laws, which would bring us back to the seventh century at least. The etymological identity of Old Irish fidchell with Old Welsh gwyddbwyll might well bring us into prehistoric times. H.J.R. Murray in his monumental History of Chess has demonstrated that "European chess is a direct descendant of an Indian game played in the seventh century with substantially the same arrangements and methods as in Europe five centuries later, the game having been adopted first by the Persians, then handed on by the Persians to the Muslim world, and finally borrowed from Islam by Christian Europe." Draughts, whatever its exact origin was, cannot be traced back beyond the thirteenth century, and some of its characteristics (viz. the board and the idea of promotion) seem to have been borrowed from chess. Thus both brandub and fidchell were current in Ireland some five centuries before the introduction of chess into Europe, and for a longer period before the invention of draughts." (Éigse vol 5 1945, p.22-35, available at: http://www.unicorngarden.com/eigse/eigse01.htm .)

|

printable version

printable version

Digg this

Digg this del.icio.us

del.icio.us Furl

Furl Reddit

Reddit Technorati

Technorati Facebook

Facebook Gab

Gab Twitter

Twitter

View Comments Titles Only

save preference

Comments (21 of 21)

Jump To Comment: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21fair play for putting the effort in but, there was a board game played by the vikings called hnefatafl (pronounced - neff - ill - taff - ill).

This game was introduced to Ireland before chess was around and it seems that chess and many other board games actually derive from hnefatafl. Google it, get a board and discover one of the best board games in the world.

So, chess was first robbed off the Vikings!

sorry, amazing story, thanks for posting it up, I hope you get a hnefatafl board

As regards hnefatafl (or tafl) don't forget the reference from the Amra Colmcille:

The main text, in capitals, was described by Colgan and is very clearly dated to the time St Colmcille died in 597. The non capitals part is from a gloss added by some scribe after that date and before 1106, the last date it could have been written into the Lebor na hUidhre (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lebor_na_hUidre ). The point is anyway that the final poem, in italics, is clearly an old poem that the scribe is using to explain that the old word 'Nia' means 'champion'. So you are back again to the time of 597 or very likely long before it, because this Cremthand Nia died in 85 AD (according to the Annals of Tigernach anyway). Also the Irish of it is easy to follow, apart from '[f]indruine,' which is a bronze like substance, that part: "Leth a foirne d'ór buide, Al leith aile d'[f]indruine", is easily and undisputably translated as "half of the team in yellow gold, and the other half in findruine." So 'fidhchell', which is the word used in the poem, cannot be identified with any kind of game like hnefatafl or tafl because they don't set up the board with an equal number of pieces on each side.Btw an Irish scribe described the whole tafl type game in an old manuscript ( http://image.ox.ac.uk/show?collection=corpus&manuscript...ms122 see also http://web.onetel.net.uk/~booksearch/hotglass/AleaEvang...i.htm ), and says it came to Ireland at the time of Athelstan who died in 939. And he doesn't make the mistake of calling it chess, he doesn't use the Irish or Latin words for chess to describe it. So hence we know all about tafl in Ireland and it is not to be mixed up with fidhchell or brannaimh, which are much older games than tafl, it is not at all the case that fidhchell or brannaimh is derived from it. So if the Vikings were doing any robbing - and they were! - it was from the Irish!

Many many thanks anyways, I am glad somebody read the thing!

Well, you seem to know your stuff. Its all very interesting, thanks again (thanks for the links)

thoroughly enjoyable read, irish folklore is terribly under appreciated for the wealth of knowledge it bestowed upon the world

and how much of it was stolen from us and re-pre-sented back to us as if belonging to someone else

great research.. bravo!!

Such a good read, I read it twice!

Thanks

Now that's a beautiful, erudite, rare labour of love you did there. I don't even play chess, and that was fascinating. Thank you.

A side question for you please, Mr. Nugent: if anybody (e.g. me) would like to reprint this - including in hardcopy - is there a way to contact you about it for permission/license (e.g. related to a possible for-profit art/craft project)?

Go raibh míle maith agat in any case for all your kind comments and good points (and to O O'Connell:

But this confusion is surprising when we are dealing with a hoard important enough to be mentioned in these minutes and only two years after its discovery. Definitely you would expect these antiquaries to know by then exactly where they were found, if they ever were on Lewis. This mysterious confusion exists to the present day bearing in mind that a major new excavation has been proposed for Méalasta, to search for the missing chessmen, a full 8 miles or so away from where they previously said the chessmen were found, in the sand dunes at Uig. (3)If its only for a bit of a craft or art thing then go ahead, I hereby give you permission! It doesn't matter if you are making a small profit on it either, its only if maybe it was a major publishing venture that copyright would be an issue I'd say...) and I just thought I would throw in another bit:

The Clonard find versus the Lewis one, too alike to be a coincidence?

In any case I was just thinking about the comparison between the Lewis chess pieces and the Queen (it seems it is a Queen, O'Donovan was wrong to assume it was a King) found at Clonard. If you look at the photograph of two Lewis Queens and the du Noyer drawing of the Clonard piece together you surely would have to agree that this Queen comes from the same set. Clearly the artist has gone for a unique and distinctive expression on her face and the placing of her hand and how likely is it that this could be by two different artists at two different periods? Realistically its by the same craftsman and also note that with respect to the Lewis find: "Madden even mentions the colour of some of the pieces ‘Dark red or beetroot’ but that the action of salt water has removed most of the colour." (1) That colour matches exactly the photograph of the Clonard piece available here: http://homepage.tinet.ie/~clonardns/thechesspiece.htm . So in all the, I suppose, three or four centuries of modern archaeological excavations and discoveries in the UK and Ireland we end up with only two examples of Celtic chessmen, finds coming within ten years or so of one another, from radically different locations but yet with exactly the same artistry. Realistically these coincidences are too great, clearly the Irish Queen and the Lewis chessmen are from the same hoard that got separated at some point. Note too that O'Donovan stated that the Clonard Queen was found with a lot of other pieces that are since lost. I respectfully submit that the only logical explanation is that these lost pieces are in fact the Lewis chessmen. You see it has always been the case that the story behind the Lewis find was suspect:

The lack of data about the Lewis find

This is an extract from the minutes of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland of the 11th March 1833, relating to the chessmen:

Hence the whole Lewis story has never been very exact. Ken Whyld, the co-author of The Oxford Companion to Chess who noted that "there is no actual proof that the pieces were found on Lewis", wrote in the British Chess Magazine of May 2003:

Sir Walter Scott

Getting back to when the pieces turned up in the UK we have this documentary evidence from the 17th October 1831 entry that Frederick Madden, Assistant Keeper of Manuscripts in the British Museum, made in his journal:

Meanwhile Scott himself wrote this in his diary for the same day: But this turned out to be only some of the Lewis collection, the rest turned up in the possession of Charles Sharpe, who just happened to be a life long friend of Scott's. This coincidence has not gone unnoticed: So in any case it has always been understood that Walter Scott is the grey eminence behind the sale of the chess pieces, if in fact he didn't own them himself, as noted e.g. in this comment: "Lewis Chess men...I believe that Sir Walter Scott ,who owned or brokered their sale" (7).

But Walter Scott is also one of the few sources who describes the Dr Tuke who owned the Irish chess piece, as he mentions here when writing to his son Walter (who then had a house neighbouring Tuke's on Stephen's Green in Dublin) on the 29th of Nov 1825:You can read more on this in the Dublin Penny Journal of the 15th of Dec 1832:Hence Walter Scott forms a kind of link between the Irish chess piece and the Lewis find in that it would surely be perfectly feasible for a friend of Scott's to discreetly arrange the sale of the chess pieces - through him - out of Ireland by passing them off as found in Scotland. But why? I hear you ask, what would be the motivation for such a swap?