The justification of James Connolly

international |

rights, freedoms and repression |

opinion/analysis

international |

rights, freedoms and repression |

opinion/analysis  Saturday May 13, 2006 09:22

Saturday May 13, 2006 09:22 by Manus O'Riordan

by Manus O'Riordan

An Easter Rising 90th anniversary lecture

CORK COUNCIL OF TRADE UNIONS

May Day commemorations

by MANUS O’RIORDAN

HEAD OF RESEARCH SIPTU

Metropole Hotel, Cork

MAY 2nd, 2006

James Connolly “Be Moderate”:

“Some men faint-hearted ever seek

Our Programme to retouch

And will insist when e’er they speak

That we demand too much.

‘Tis passing strange, yet I declare

Such statements cause me mirth,

For our demands most modest are:

We only want the Earth!

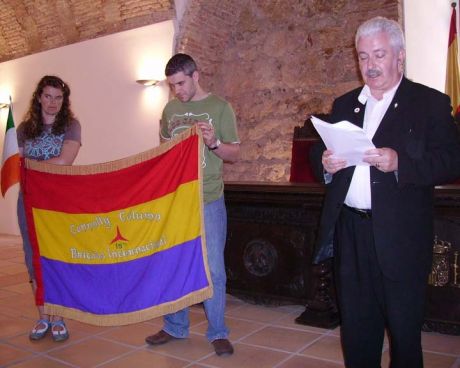

PHOTOGRAPH

COMMEMORATIVE ADDRESS ON JAMES CONNOLLY AND TERENCE McSWINEY BY MANUS O'RIORDAN ON EASTER SUNDAY 2006 AT THE FORTRESS OF CASTELL DE SANT FERNAN, FIGUERES, CATALONIA. (see linked story)

THE JUSTIFICATION OF JAMES CONNOLLY

In the first place I want to congratulate the Cork Council of Trade Unions for organising this commemorative lecture in memory of James Connolly. I am also honoured that preceding me as a speaker on this platform this evening has been Robert McBride of South Africa’s African National Congress. Now the Chief of Police for Johannesburg’s East Rand district, Robert McBride has come a long way from when he languished as a prisoner under sentence of death on Apartheid’s death row. He has publicly acknowledged that it was the solidarity campaign organised on his behalf here in Ireland that probably saved his life, as it drew attention to the role of his great-grandfather Major John McBride in leading an Irish Brigade in defence of the Boer Republics against Britain. Robert McBride has also drawn attention to yet another act of solidarity worthy of note. As a former hunger striker himself in the prisons of South Africa, he has told us that when the Lord Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney, died on hunger strike in a British prison in October 1920, the then General Secretary of his own African National Congress sent a message of solidarity to Sinn Féin - from one fledging liberation movement to another.

But Robert McBride’s own ancestor had also played a key role in the revival of the national movement here in this city of Cork itself, in the aftermath of the disastrous split in the Irish Volunteers that had been brought about by John Redmond’s support for Britain’s Imperialist War in 1914. It was on the occasion of the Manchester Martyrs’ Commemoration of November 1914 that an inspirational address by Major John McBride at a Cork City Hall rally put fire in the belly of Cork Republicans once again and enabled Tomás MacCurtain and Terence MacSwiney to rebuild the Irish Volunteers in both city and county.

Cork Council of Trade Unions has correctly recognised the hunger of the Irish people to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the proclamation of an Irish Republic in Easter 1916, as well as of a Rising subsequently endorsed by the Irish electorate in the December 1918 General Election. Such commemorations can be many and varied. This Easter Sunday I myself spoke at a 70th anniversary International Brigade commemoration in Catalonia which not only included a commemoration of the Easter Rising but where I also drew attention both to the demonstrations of solidarity with Terence MacSwiney that were held in Catalonia in 1920 and to the reciprocal solidarity shown by his widow Muriel MacSwiney in 1936-39 when, as a member of the Communist Party of France, she demonstrated her own solidarity with the Spanish Republic in its struggle against Fascism.

This very night is the eve of t he 90th anniversary of the first set of executions of 1916 leaders - those of Patrick Pearse, Thomas Clarke and Thomas McDonagh on May 3rd. They were followed, among others, by those of John McBride on May 5th and of my own Union’s leader James Connolly on May 12th.

It is the justification of James Connolly that is the subject-matter of this lecture – a man still denounced by his enemies of today as “a war criminal”, because of his support for Germany in the 1914 War, and as “a bloodthirsty Marxist”, because of his leadership of the 1916 Rising. How then to respond to such attacks?

Connolly should neither be deified nor have myths constructed around him. But what of Connolly’s stand on the First World War? His 1961 biographer C.D. Greaves maintained that “Connolly’s thought ran parallel with Lenin’s”. But this was simply not true. Thirty years ago a controversy raged in the columns of the “Irish Times” during which I challenged the prevailing view that Connolly’s position in respect of the First World War had been one of neutrality. I also pointed out that it was not Lenin who appealed to Connolly, but rather the Russian Bolshevik leader Lenin’s life-long opponent, the Polish Socialist leader Josef Pilsudski. Connolly in fact applauded Pilsudski’s Polish Legion for fighting alongside Germany against Russia, as a contingent of the Austrian army. (“ Worker’s Republic”, April 15th, 1916).

In 1976, while holding that the 1916 Rising had been justified, I had nonetheless also gone on to criticise Connolly for not ideologically differentiating himself to a sufficient degree from his allies and for violating the “pure” socialist principle of neutrality in respect of the Imperialist War. A re-assessment of Connolly on my part also involves a re-assessment of what I myself previously wrote about him. The more I re-read Connolly the more convinced I am that I got it right as to where he stood on the First World War. It was, however, when I held Connolly to have been wrong for taking such a stand, that I myself got it wrong. The more I now read Connolly in conjunction with the actual history of the First World War itself the more I appreciate his reasons for rejecting neutrality in that conflict and for preferring a German victory over a British one.

Those who wish to remain convinced of Connolly’s neutrality always allude to a particular slogan of his – “We Serve Neither King nor Kaiser but Ireland” – that Connolly hung as a banner from Liberty Hall and used as the masthead of the “Irish Worker” from the end of October to early December 1914. This, in my view, was little more than an example of a Connolly pose, a device that he sometimes adopted as a public stance in order to enable him to operate more effectively with a different agenda.

One has only to read the detail of what Connolly actually wrote from 1914 to 1916 to realise that his supposed wartime neutrality was such a pose. Connolly’s very first article on the outbreak of that War - “Our Duty in the Crisis” (“Irish Worker”, August 8th, 1914) explicitly stated:

“Should a German army land in Ireland tomorrow we should be perfectly justified in joining it, if by doing so we could rid this country once and for all from its connection with the Brigand Empire that drags us unwillingly into this War”.

But what of Connolly’s disregard of the issue of German atrocities in Belgium? In total, 5,500 Belgian civilians are estimated to have been deliberately killed by the German army. Connolly did not, however, accept British propaganda concerning these atrocities because such propaganda had become so wildly exaggerated as to become utterly incredible. Pre-war photographs of Russian pogroms against the Jews – by Britain’s Tsarist wartime ally! – were being reprinted in the British press as supposed illustrations of German atrocities in Belgium. Britain also falsely accused the Germans of cutting off the hands of Belgian children. These particularly false accusations nauseated Connolly all the more. Not only had such child mutilations never been experienced by Belgium, they in fact mirrored what Belgium itself had been inflicting on the people of the Congo. In his article “Belgian Rubber and Belgian Neutrality” (“Irish Worker”, November 14th, 1914) Connolly expressed outrage at how quickly Britain had chosen to forget Roger Casement’s exposure, only a decade previously, of Belgian genocide against the Congolese. Having had an intimate knowledge of the Congo from an earlier visit in 1886, Casement found the 1903 devastation to be truly horrific. Where he had known one particular community of 5,000, he could now find only 600 survivors. Other areas he had previously visited, when they had a population of 40,000, he now found reduced to 8,000 inhabitants. It was only in 1919 that an official Belgian Government Commission conceded that since the beginning of Belgian rule in the Congo in 1885 its population had been cut by a half, or 10 million people. Such wholesale genocide was the Belgian atrocity that most concerned Connolly.

But to return to the causes of the First World War. Connolly argued in his article entitled “The War Upon the German Nation” that it was as an economic rival that Britain wanted Germany crushed. (“Irish Worker”, August 29th, 1914). To further that objective the British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey had in fact told Clemenceau of France in April 1908 that it was his policy to reinforce Tsarist Russia as a “counterpoise to Germany on land”. A strengthened Russia would in turn threaten Germany’s ally Austria, and Grey sanctioned Russia’s sponsorship of expansionist Serbian nationalism for that purpose. And damn the consequences.

James Joyce, who had lived under the Austrian Empire in Trieste, would, in a post-war letter to Mary Colum, dismiss Britain’s anti-Austrian propaganda with the observation: “They called the Austrian Empire a ramshackle empire … I wish to God there were more such empires”. Britain wanted that Empire broken up, no matter what, and in fact expressed anger that Russia had not reacted more firmly in 1908 against Austria’s formal incorporation of the Bosnia it had ruled since the collapse of Ottoman rule in that province in 1878.

Serbia, of course, wished to rule Bosnia as part of a Greater Serbia, irrespective of the fact that the majority of Bosnians were opposed to any such outcome. In 1914 Croats, Muslims, Slovenes, Croatian Serbs - and even a minority of Bosnian Serbs - would all fight in the Austrian army against Serbia. And the spark that came from that conflict set alight the Inferno that engulfed Europe for the next four years. Following the conclusion of the World War in November 1918, when Serbia had finally conquered Bosnia, Britain’s ally went on to celebrate its triumph in the New Year of 1919 with the massacre of 1,000 Muslim men, the burning to death of seventy-six Muslim women and the pillaging of 270 villages.

We are still living today with the consequences of the forces that Britain set out to unleash in Europe a century ago. When the UCD Professor of Economics and Redmondite MP Tom Kettle launched his war propaganda on behalf of Britain with an article entitled “Europe Against The Barbarians” (“Daily News”, August 10th, 1914), it was to give Serbia a free hand to do whatever she wanted to do in the Balkans, while Britain got to grips with the bigger picture:

“As for Serbia, it seems probable that nobody will have the time to go to war with her. Her function has been that of the electric button which discharges the great gun of a fortress. And now that the lightenings have been released, what is the stake for which we are playing? It is as simple as it is colossal. It is Europe against the barbarians … The ‘big blonde brute’ has stepped from the pages of Nietzsche out on to the plains about Liege”.

On February 23rd, 1916 the British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith was to declare: “We shall not sheath the sword … until Belgium – and I will add Serbia – recovers in full measure all, and more than all she has sacrificed”. And in June 1916 that Government made sure that ‘Kosovo Day’ was celebrated in honour of the Serbs throughout the length and breadth of Britain.

The British Government knew perfectly well the character of the forces it was supporting. The Balkan Wars had commenced in October 1912 following a revolt against Ottoman rule both in Albania itself and by the Albanian majority in Kosovo. Serbia then attacked in order to annex not only Kosovo but also the coastal territory of Northern Albania. Austria forced Serbia to withdraw from Albania proper and concede its independence. But Serbia hung on to Kosovo, having massacred anything between 20,000 and 25,000 Albanian civilians by December 1912.

These massacres had been recounted at the time in eye-witness reports by Edith Durham in the English-speaking press, by Leon Trotsky in the Russian-speaking press, and by a host of newspaper reports right across Europe. The massacres in Kosovo were also confirmed by a Carnegie Commission Report co-authored by the editor of “The Economist”, H.N. Brailsford. This 1913 Report spoke of “houses and whole villages reduced to ashes, unarmed and innocent populations massacred en masse, incredible acts of violence, pillage and brutality of every kind – such were the means which were employed and are still being employed by the Serbo-Montenegrin soldiery, with a view to the entire transformation of the ethnic character of regions inhabited exclusively by Albanians”. And so it was that both Kettle and Asquith were made fully aware beforehand as to what was in store for the Balkans when they went on to unequivocally champion Serbia’s War in 1914.

While Kettle was whipping up Irishmen to enlist in Britain’s War against Germany, Connolly issued a manifesto in the name of the Irish Citizen Army that pointed out:

“Remember, all you workers, that this war is utterly unjustifiable and unnecessary. Belgium would never have been in the slightest danger if France had not encouraged Russia to prepare to attack Germany. And France would not have given that encouragement to Russia had she not been urged to do so by the secret diplomacy of England. There would never have been a war within two hundred and fifty miles of the Belgian frontier had not the French and English Governments secretly resolved to attack Germany in order to help Russia – the greatest and most brutal foe of human liberty in the world”. (“Irish Worker”, August 15th, 1914).

When James Connolly categorised British policy in August 1914 as “The War Upon the German Nation”, it was also a war upon any German national who could be found. It is a remarkable fact that all of the historians and journalists who have sought to re-create and celebrate Irish involvement in England’s Imperialist War have either overlooked or studiously ignored one very dramatic event during the first fortnight of that War – the Dublin pogrom of August 15th, 1914. Between 11 and 11.30 that night a wave of mob attacks on German pork butcher shops occurred across Dublin. The most serious were on the premises of Frederick Lang in Wexford Street and George Reitz at Leonard’s Corner on South Circular Road, Portobello. These attacks were particularly frightening because they were conducted by the same mob making it’s way from one premises to the other, requiring a walk of at least twenty minutes. All the more sinister was the fact that this mob, hell-bent on destruction and pillage, was led by a newly-enlisted soldier who had answered John Redmond’s and Tom Kettle’s call to arms and who first wished to fight the “barbarians” in our midst before embarking for the War on the Continent. Not only were both shop premises totally wrecked, but the upstairs living quarters of Lang and his family and staff had also been invaded and their furniture smashed up and thrown out the window. Lang himself was arrested and interned, and his family impoverished.

The fullest account of the attack on George Reitz’s premises appeared in the “Irish Worker” on August 22nd, 1914. Under the heading of “German Baiting: The Police Cowardice” the correspondent described a classic pogrom scene. Having first arrested Reitz himself, the Dublin Metropolitan Police then left his premises unprotected and allowed the mob to proceed unhindered in destroying that shop and robbing its contents. Meanwhile, the DMP themselves stood “idly by” and laughed away the night as they observed the “sport” of the Redmondites plundering to their hearts content.

But the “Irish Worker” of Larkin and Connolly let it be clearly understood that if the homes of “citizens of German extraction” were to face the threat of any further pogroms, “an appeal to the men of the Transport Union and the Citizen Army to act as a guard for their houses would not fail to produce good results”. In writing in the same issue, the Aran Islander Micheál Ó Maoláin, an organiser for both the Irish Transport and General Workers Union and the Irish Citizen Army, went on to observe:

“One of the most distinguished gentlemen upon whom the Freedom of this City was recently conferred was a German – Dr. Kuno Meyer … (for his) work in the saving of the Irish language. He was then acclaimed as a public benefactor, but now it seems that were he found in our streets he would be apprehended … and perhaps his residence looted by the King’s Irishry”.

Ó Maoláin was not far wrong. Kuno Meyer was the German Celtic scholar who had founded the Dublin School of Irish Learning in 1903. On March 15th, 1915 Dublin City Council voted to deprive Meyer of the Freedom of the City it had previously bestowed on him in April 1912 – an act also denounced by Ó Maoláin in Connollys “Workers Republic” on November 6, 1915. And Meyer was to be similarly punished by Cork City Council in striking out the Freedom of the City that it had bestowed upon him in September 1912. Meyer was to die in October 1919. While Dublin City Council would in April 1920 posthumously rescind its vindictive vote of five years previously, Cork City Council never got around to it.

The anti-German racism of the British state had also visited Cork in a particular way in 1916 when it struck at the family of six-year old Aloys Fleischmann, described by his life-long friend and Cork’s first Jewish Lord Mayor Gerald Goldberg as “the only child born to Herr Aloys and Frau Tilly Fleischmann, the one a choir master, the other a consummate pianist, and later teacher, who in her youth had been a pupil of a pupil of Liszt”. Tilly Swertz had been born to Bavarian parents in Cork, where her father held the position of organist at the North Cathedral since the 1870s, and she in turn married another Bavarian, Aloys Fleischmann Snr., who also went on to become the Cathedral’s organist and choirmaster.

During the first two years of the Imperialist War the Fleischmanns had been successfully shielded by their Cork Republican friends from British state racism. In 1916, however, Aloys Snr. was arrested as an “enemy alien” and transported to an internment camp in England, while Tilly was compelled to close the family home. Their real crime was how patriotically Irish these Germans had actually become. It was in fact in the Fleischmann home that the future Republican Lord Mayor and Lady Mayoress of Cork, Terence and Muriel MacSwiney, had first met each other in 1915. The German internee’s son, Aloys Fleischmann Jnr., went on to become Professor of Music at University College Cork, founder of the Cork Symphony Orchestra, co-founder of the Cork Ballet Company and founder of the Cork International Choral Festival.

The pogromist attack on George Reitz’s shop in the Dublin neighbourhood of Leonard’s Corner rang particular alarm bells for that city’s Jewish community, since Leonard’s Corner was where the Lower Clanbrassil Street thoroughfare of kosher and other Jewish shops commenced. Had that particular mob not been fully sated and exhausted by attacking in succession two widely separated German shops, there can be little doubt that the Jewish shops adjacent to Reitz’s would have been treated as the next sitting targets. Anti-Semitic outbursts would not have been a novel feature for a Redmondite mob. At the February 1909 Convention of the United Irish League, where John Redmond had denied free speech to Cork MP William O’Brien and had driven him out of the Party, and the AOH toughs were under instruction not to let anybody near the speaker’s podium who had “a Cork accent”, the great cry of Redmond’s Hibernian bully-boys had been “Down with the Russian Jewess!” - with reference to O’Brien’s wife, Sophie Raffalovich. Moreover, in the two days prior to the anti-German pogrom in Dublin the press had made it clear that the xenophobia against aliens that British war hysteria was now whipping up would make little distinction between German and Jew. The headline in the “Irish Independent” of August 13th ran:

“Germans in Ireland – Looking for the Spies – Wholesale Arrests in Dublin – Russian Jews Arrested”.

It was reported that two Russian Jewish pedlars had been arrested in Mullingar and another Russian Jew in Fermoy, one of the three continuing to be held in detention. On August 14th the “Irish Independent” also described another arrested Jew as a Russian Pole when, under the heading of “Thurles Anti-German Feeling”, it reported:

“Included in the arrests reported yesterday was a Russian Pole named Marcus … On being arrested at Thurles, where he had been 3 years, Ernest Krantz, a jeweller, was booed and jeered at, amidst loud cries of ‘Down with Germany’, and the police had difficulty in saving him from being mobbed”.

The anti-historical telescoping of the First and Second World Wars has succeeded in obscuring the fact that, in the 1914 War between Britain and Germany, it was Britain - in alliance with Tsarist Russia - that represented the forces of anti-Semitism. As Niall Ferguson points out in The Pity of War, when Lord Rothschild implored the London “Times” on July 31st, 1914 to tone down its leading articles, that were '‘hounding the country into war”, both the foreign editor Henry Wickham Steed and his proprietor Lord Northcliffe described this plea as “a dirty German-Jewish international financial attempt to bully us into advocating neutrality” and concluded that “the proper answer would be a still stiffer leading article tomorrow”.

The anti-Semitic hysteria of the British Establishment had its greatest impact in Ulster. In Jews in Twentieth Century Ireland Dermot Keogh has brought to light the fact that Sir Otto Jaffe, Belfast’s only Jewish Lord Mayor, who had held that office in both 1899 and 1904, was compelled to resign his seat on Belfast City Council and flee Ulster in 1916. Despite the fact that this Life-President of the Belfast Jewish Congregation had lived in Ulster for over sixty years, that he had funded the establishment of a physiology laboratory in Queen’s University Belfast and that he had both a son and a nephew serving in the British army that was waging war on Germany, his own German birth now made Jaffe a marked man among his fellow-Unionists. If in April 1920 Dublin City Council could belatedly but unanimously make amends to the memory of the now-deceased Kuno Meyer, perhaps a more enlightened Belfast City Council might yet do the same for Otto Jaffe.

Russian-born but Newry-reared Leonard Abrahamson observed in 1914 that “the virus of anti-Semitic feeling, born of ignorance and fostered by unrelenting prejudice, still courses in the veins of numerous – if not the majority – of Britishers”. And Leonard’s own father became the target of such anti-Semitism. Never in his life had he had the remotest connection with Germany. But this mere fact was not to spare David Abrahamson from being subjected to the “anti-German” attacks of Ulster’s Empire Loyalists in both Newry and Bessbrook. Leonard further observed:

“Since the outbreak of the war, the belief generally rampant that all Jews are Germans, has given rise to many unpleasant and reprehensible occurrences. Not only has this erroneous notion gained ground amongst the uneducated but it has been fostered by the repeated linking in several journals – amongst others, the ‘Times’ – of the term Jew and German”.

Such experiences only served to accelerate Leonard Abrahamsons’s own development as an Irish Nationalist. As honorary librarian of Trinity College Dublin’s Gaelic Society, and signing himself Mac Abram, he was to be disciplined in November 1914 by the University’s Provost John Pentland Mahaffy for daring to invite “a man called Pearse” to speak from its platform, to whom Mahaffy particularly objected because “he was a declared supporter of the anti-recruiting agitation” against Britain’s War-effort. The occasion was to have been a Thomas Davis Centenary lecture by W.B. Yeats, with Tom Kettle requested to propose the vote of thanks and Patrick Pearse to second it. Barred from Trinity, Abrahamson and his colleagues were determined to retain Pearse as a speaker, and so they reconvened the meeting with a new venue in the Antient Concert Rooms on November 20th. British army recruiting officer Kettle arrived in uniform at the meeting quite drunk, and was booed both for his recruiting activities and his drunkenness. Pearse sang the praises of John Mitchel as well as Davis. And Yeats, while criticising both the Unionism of Mahaffy and the pro-Germanism of Pearse, also went on to take a stand against Kettle’s hate-campaign against German culture.

Central to Connolly’s propaganda against Britain’s War was his exposure of anti-Semitism. This was no overnight conversion on Connolly’s part. If we are to assess the whole array of Irish leaders of the past century, Connolly stands head and shoulders above everybody else in his commitment to a pluralist Ireland that should also welcome the Jewish immigrant. In my 1988 study Connolly Socialism and the Jewish Worker that was published in “Saothar”, Journal of the Irish Labour History Society, I pointed out Connolly’s unique place in history as the only Irish politician ever to have published an election address in the Yiddish language. This was during the 1902 local elections when he sought the support of the immigrant Jewish workers who had fled to Dublin as refugees from Tsarist Russian pogroms. His Redmondite opponents responded by putting it about among Christian voters that Connolly must therefore have been a Jew himself!

From the very outset of the War, Connolly was to denounce Britain’s alliance with the powerhouse of anti-Semitism in Europe, Tsarist Russia. He described that Empire’s massacres as follows:

“In these pogroms the Jewish districts were given up to pillage and outrage by mobs of armed men, while the police looked calmly on. Shops and houses were burned after being looted, women and children were ravished, babies and old men were thrown from windows to their death in the streets and hell was let loose generally upon the defenceless people”. (“Irish Worker”, August 22nd, 1914).

This was a theme continued by Connolly a month later in his article “The Friends of Small Nationalities” (“Irish Worker”, September 12th, 1914). He quoted the following from the New York Yiddish daily newspaper “Warheit”:

“The question is, on what side must we Jews sympathise? Where do our interests lie? The very question suggests the answer. At the present time there are only three nations in the whole of Europe whose people are not entirely antagonistic to the Jews. These countries are Austria-Hungary, Germany and Italy. Never have they been so much hated, persecuted and despoiled in any countries as in Russia, Roumania, and Greece … Even the English have lately begun to hate and persecute the Jews, while in France even their household life is made unbearable. All these considerations naturally incline us to one side. Cursing those who have now compelled Jew to fight Jew, and war in general, we hope and pray that the Austrian and German arms will be victorious in the struggle”.

And so Connolly continued to agitate in the remaining two years of his life. In the “Workers Republic” on September 18th, 1915 he highlighted the fact that anti-Semitism had become rampant in France and that it was regarded as tantamount to treason to fight against it, while “in Russia the government is getting ready to stain its hands with more Jewish massacres; blaming the failure of the Russian armies … upon the Jews”. And a week before the Easter Rising, in an article entitled “Russia and the Jews”, he again exposed the genocidal character of Tsarist pogroms (“Workers Republic”, April 15th, 1916).

This was not just alarmist propaganda on Connolly’s part. History has proved him right. Martin Gilbert’s First World War tells it like it was as the Russian troops pushed deeper into Austrian Galicia in 1914: “In the zone of the Russian armies, according to (one of the principal architects of the War) the French Ambassador to Russia, Paléologue, Jews were being hanged every day, accused of being secretly sympathetic to the Germans and wanting them to succeed… Hundreds of thousands of Jews were driven from their homes in Lodz, Piotrkow, Bialystok and Grodno, and from dozens of other towns and villages”.

The same was to happen in the Baltic region in March 1915:

“Russian Cossacks, the traditional enemies of the Jews since the seventeenth century, forced them out of their homes and drove them through the snow. As many as a half a million Jews were forced to leave Lithuania and Kurland”.

The situation worsened further during the Russian retreat of Summer 1915. Norman Stone’s study, The Eastern Front 1914 – 1917, described how the Tsarist army proclaimed a ‘scorched earth’ policy that was very selectively applied indeed: “In practice, this meant merely a heightened degree of anti-Semitism”. Stone further revealed how the British Government had kept itself fully briefed concerning the atrocities being committed by its great ally. On August 4, 1915 a War Office official named Blair provided his London superiors with the following on-the-spot assessment from Russia: “Even the most extreme anti-Semites have been moved to complain at treatment of the Jews”. Yet Britain itself did not complain. Instead, Sir Winston Churchill would go on to pen an uncritical hymn of praise entitled The Unknown War, which he dedicated to the Tsarist army.

But the English-speaking public at large did not need to await the subsequent researches of historians for a clear exposure of the horrors that were being perpetrated behind the Russian lines. America’s top correspondent John Reed – later to achieve even greater fame for his Ten Days That Shook The World account of the 1917 Russian Revolution - had reported on this dark subject for the “Metropolitan Magazine” during 1915 itself, and his dispatches were subsequently published in book form in 1916 under the title of War in Eastern Europe – Travels through the Balkans in 1915.

As he travelled through Russian-occupied territory, Reed was horrified by what he found among the ruins of the Jewish quarter of Austrian Novo Sielitza: “The Russians had wrecked everything at the beginning of the war – what became of the people we didn’t like to think”. Moving northward through Bukovina he described the villages he found: “Many houses were deserted, smashed and black with fire – especially those where Jews had lived. They bore marks of wanton pillage - for there had been no battle here – doors beaten in, windows torn out, and lying all about the wreckage of furniture, rent clothing. Since the beginning of the war the Austrians had not come here. It was Russian work …”

In the town of Zalezchik, “an atmosphere of terror hung over the place – we could feel it in the air. It was in the crouching figures of the Jews, stealing furtively along the tottering walls.” These were the survivors of the massacre described to Reed by a Jewish pharmacist who had also survived: “A month ago the Russians came in here – they slaughtered the Jews, and drove the women and children out there” – westwards. And in the town of Tarnapol there were three Russian soldiers to every civilian. “Many Jews had been ‘expelled’ when the Russians entered the town – a dark and bloody mystery that”. Reed summed up the Tsarist Russian mind-set as one that would do its best “to exterminate the Jews”.

This, then, was the ally that Britain wished to see triumphant in the East. In Britain’s grand scheme of things for Europe, tens of thousands of exterminated Jewish civilians were as expendable as their Albanian counterparts in Kosovo.

“Degradation” was the term that Connolly had used time and time again to describe the enlistment of Irish support for Britain’s War. And he was not just referring to the sacrifice of 35,000 Irish lives in the actual warfare itself. He was also referring to the degradation of Irish society by all the anti-Semitic and anti-German racism that was central to the British war effort. Ending such degradation ranked high among the objectives for which he planned the 1916 Rising.

Connolly’s stand on the War also comes under attack in more indirect ways, through the creation of alternative heroic myths on the other side of the Great War divide. Francis Ledwidge is often extolled not only for his poetry and personal courage but also for the cause for which he enlisted in the British army. Ledwidge, who fought in Kosovo in 1915 in order to expel the new Bulgarian invaders and restore that province to the only slightly more recent Serbian invaders of 1912, has been frequently quoted with approval for the anti-German sentiments contained in his statement that “I joined the British Army because she stood between Ireland and an enemy common to our civilisation and I would not have it said that she defended us while we did nothing at home but pass resolutions”. But this statement is usually quoted out of context. Alice Curtayne’s biography – Francis Ledwidge, A Life of the Poet - makes it perfectly clear that it is taken from a June 1917 letter in which Ledwidge, while no longer adhering to such a view, explained what had been his original motivation for enlisting in 1914. In that same letter Ledwidge revealed his sympathies for the 1916 Rising, referred to his poem on the executed Rising leader Thomas McDonagh as his favourite one, and described how awful it felt to be “called a British soldier while my own country has no place among the nations but the place of Cinderella”. Home on leave in the immediate aftermath of the Easter Rising Ledwidge had in fact told his brother Joe: “If I heard the Germans were coming in over our back wall, I wouldn’t go out now to stop them. They could come!”

Francis Ledwidge died on the wrong side. His personal tragedy lies primarily in the fact that he himself knew that to be the case.

But there was nothing so purposeless about either the life or death of James Connolly. As he said to his daughter Nora on May 9th, 1916:

“It was a good clean fight. The cause can’t die now. The fight will put an end to recruiting. Irishmen now realise the absurdity of fighting for another country when their own is enslaved”.

And on the morning of his execution on May 12th when his wife Lilly had cried out in anguish – “But your beautiful life, Jim, your beautiful life!” – Connolly said to her: “Wasn’t it a full life Lilly, and isn’t this a good end?”

But what, then, of Connolly’s Socialism?

In The Story of the Irish Citizen Army Seán Ó Casey maintained that on the road to the 1916 Rising “Connolly had stepped from the narrow byway of Irish Socialism onto the broad and crowded highway of Irish Nationalism … Connolly was no more an Irish Socialist martyr than Robert Emmet, P.H. Pearse, or Theobold Wolfe Tone”.

I disagree with O’Casey.

The appropriate question to ask is whether or not Connolly had made amply clear during the 1914-16 period that he still adhered to his pre-War socialist convictions. In answering that question we also need to clarify what those socialist convictions were, since there is a Redmondite school of commentary that seeks to caricature and damn Connolly on all scores. One particular example of this was offered by the “Irish Times” of May 10th, 2001 in the following outburst from Kevin Myers:

“Connolly … much to Kaiser Bill’s pleasure, started bumping people off in the centre of Dublin … This is the only free country in the world where a bloodthirsty proponent of violent Marxism is still spoken of with respect”.

But as far back as his article in the “Shan Van Vocht” of August 1897 Connolly had made it perfectly clear that “in an independent country the election of a majority of Socialist representatives to the Legislature” was the democratic precondition required for “the gradual extinction” of the rule of the propertied classes and “the work of social reconstruction”.

There was nothing “bloodthirsty” or “violent” about Connolly’s Marxism. In “L’Irlande Libre” in 1897 he outlined his conception of Socialism as follows:

“Scientific Socialism is based upon the truth incorporated in this proposition of Karl Marx, that, ‘the economic dependence of the workers on the monopolists of the means of production is the foundation of slavery in all its forms, the cause of nearly all social misery, modern, crime, mental degradation and political dependence’… Since the abandonment of the unfortunate insurrectionism of the early Socialists whose hopes were exclusively concentrated on the eventual triumph of an uprising and barricade struggle, modern Socialism, relying on the slower, but surer method of the ballot-box, has directed the attention of its partisans toward the peaceful conquest of the forces of Government in the interests of the revolutionary ideal. The advent of Socialism can only take place when the revolutionary proletariat, in possession of the organised forces of the nation (the political power of Government) will be able to build up a social organisation in conformity with the natural march of industrial development..."”

“(1) We hold ‘the economic emancipation of the worker requires the conversion of the means of production into the common property of Society’. Translated into the current language and practice of actual politics this teaches that the necessary road to be travelled towards the establishment of Socialism requires the transference of the means of production from the hands of private owners to those of public bodies directly responsible to the entire community.

(2) Socialism seeks then in the interest of the democracy to strengthen popular action on all public bodies”.

Moreover, in an article entitled “Physical Force in Irish Politics”, Connolly met this issue head-on in the “Workers’ Republic” of July 22nd, 1899:

“The Socialist Republican conception of the functions and uses of physical force is: We neither exalt it into a principle nor repudiate it as something not to be thought of. Our position towards it is that the use or non-use of force for the realisation of the ideas of progress always has been and always will be determined by the attitude, not of the party of progress, but of the governing class opposed to that party. If the time should arrive when the party of progress finds its way to freedom barred by the stubborn greed of a possessing class entrenched behind the barriers of laws and order; if the party of progress has indoctrinated the people at large with the new revolutionary conception of society and is therefore representative of the will of a majority of the nation; if it has exhausted all the peaceful means at its disposal for the purpose of demonstrating to the people and their enemies that the new revolutionary ideas do possess the suffrage of the majority; then, but not till then, the party which represents the revolutionary idea is justified in taking steps to assume the powers of Government, and in using the weapons of force to dislodge the usurping class or Government in possession, and treating its members and supporters as usurpers and rebels against the constituted authorities … The ballot-box was given us by our masters for their purpose; let us use it for our own. Let us demonstrate at the ballot-box the strength and intelligence of the revolutionary idea; let us make the hustings a rostrum from which to promulgate our principles; let us grasp the public powers in the interest of the disinherited class …”.

Connolly’s conception of a Socialist society underwent further development and deepening during his period in the United States of America and found expression in his 1908 series of lectures subsequently published under the title of Socialism Made Easy. He wrote:

“Social-Democracy, as its name implies, is the application to industry, or to the social life of the nation, of the fundamental principles of democracy. Such application will necessarily have to begin in the workshops, and proceed logically and consecutively upward through all the grades of industrial organisation until it reaches the culminating point of national executive power and direction. In other words, Socialism must proceed from the bottom upward whereas capitalist political society is organised from above downward … ”

“It will be seen that this conception of Socialism destroys at one blow all the fears of a bureaucratic state, ruling and ordering the lives of every individual from above, and thus giving assurance that the social order of the future will be an extension of the freedom of the individual, and not a suppression of it”.

Connolly belonged neither to the Soviet nor the British schools of State Socialism. But what happened Connolly’s Marxism during the First World War? Did he abandon this explicitly Social-Democratic perspective to become instead “a bloodthirsty proponent of violent Marxism”, or did he abandon Socialism altogether for the “Physical Force” Nationalism whose mystique he had previously challenged? He did neither. Britain’s War had by definition closed off all peaceful options until that War should be brought to a conclusion. And it was the “Rule Britannia, Britannia Rules the Waves” basis of that War that had closed off the possibility not only of Socialism itself but also of free industrial development in its capitalist form. It was not merely as an Irish Republican but also as an International Socialist that Connolly sought Britain’s defeat. Only a month short of the Easter Rising, in the “Workers’ Republic” of March 18th, 1916, Connolly argued in an article entitled “The German or the British Empire”:

“Every Socialist who knows what he is talking about must be in favour of freedom of the seas, must desire that private property shall be immune from capture at sea during war, must realise that as long as any one nation dominates the water highways of the world neither peace nor free industrial development is possible for the world. If the capitalists of other nations desire the freedom of the seas for selfish reasons of their own that does not affect the matter. Every Socialist anxiously awaits and prays for that full development of the capitalist system which can alone make Socialism possible, but can only come into being by virtue of the efforts of the capitalists inspired by selfish reasons … We do not wish to be ruled by either Empire, but we certainly believe that the first named contains in germ more of the possibilities of freedom and civilisation than the latter”.

If we might borrow the language of the great split that occurred in the Russian Socialist movement a century ago, Connolly was an Irish Menshevik rather than an Irish Bolshevik. He held that the political pre-requisite for constructing a Socialist society was the democratic mandate of majority support. But, no less importantly, he also held that the economic pre-requisite was that such a society should be built on foundations established by the full development of the capitalist system. On the eve of the Easter Rising Connolly nailed his socialist colours to the mast - the colours of evolutionary socialism.

The circumstances of Britain’s Imperialist War, however, dictated that as far as the issue of Irish independence was concerned, revolutionary methods were now called for. Not satisfied with the fact that tens of thousands of Irishmen in the British Army were already sacrificing their lives, British Imperialist blood lust would soon confront Ireland with the threat of conscription.

Connolly argued:

“They who now would oppose conscription must not delude themselves into the belief that they are simply embarking upon a new form of political agitation, with no other risks than attend political agitation in times of peace … (If) the British ruling class has made up its mind that only conscription can save the Empire … it will enforce conscription though every river in Ireland ran with blood … Our rulers will ‘stop at nothing’ to attain their ends. They will continue to rule and rob until confronted by men who will stop at nothing to overthrow them”. (“Workers’ Republic”, November 27th, 1915).

Connolly further declared:

“We believe in constitutional action in normal times; we believe in revolutionary action in exceptional times. These are exceptional times”. (“Workers’ Republic”, December 4th, 1915).

Early in the New Year of 1916 Connolly proceeded to issue a public call to the Irish Volunteers to join with his Irish Citizen Army in taking the necessary action:

“It is our duty, it is the duty of all who wish to save Ireland from such shame or such slaughter to strengthen the hand of those of the leaders who are for action as against those who are playing into the hands of the enemy. We are neither rash nor cowardly. We know our opportunity when we see it, and we know when it has gone”. (“Workers’ Republic, January 22nd, 1916).

The title of that editorial is “What Is Our Programme?” and in it is embodied Connolly’s constructive legacy. It is a remarkable document in so many different ways. For it was in this very Programme in which he issued the call for a 1916 Rising that Connolly also made it quite explicit that he was doing so as a Socialist who would never lose sight of his vision of a new society:

“The Labour movement is like no other movement. Its strength lies in being like no other movement … Other movements dread analysis and shun all attempts to define their objects. The Labour movement delights in analysing, and is perpetually defining and re-defining its principles and objects … What is our Programme? We at least, in conformity with the spirit of our movement, will try and tell it. Our programme in time of peace was to gather into Irish hands in Irish trade unions the control of all the forces of production and distribution in Ireland. We never believed that freedom would be realised without fighting for it. From our earliest declaration of policy in Dublin in 1896 the editor of this paper had held to the dictum that our ends should be secured ‘peacefully if possible, forcibly if necessary’ … We believe that in times of peace we should work along the lines of peace to strengthen the nation, and we believe that whatever strengthens and elevates the working class strengthens the nation”.

Britain’s Imperialist War, however, confronted Ireland with a challenge that had now to be met with firm resolve:

“But we also believe that in times of war we should act as in war. We despise, entirely despise and loathe, all the mouthings and mouthers about war who infest Ireland in time of peace, just as we despise and loathe all the cantings about caution and restraint to which the same people treat us in times of war. Mark well then our programme. While the War lasts and Ireland still is a subject nation we shall continue to urge her to fight for her freedom. We shall continue, in season and out of season, to teach that the ‘far-flung battle line’ of England is weakest at the point nearest its heart, that Ireland is in that position of tactical advantage, that a defeat of England in India, Egypt, the Balkans or Flanders would not be so dangerous to the British Empire as any conflict of armed forces in Ireland, that the time for Ireland’s battle is NOW, the place for Ireland’s battle is HERE …”.

Yet never was such a call to arms accompanied by such outright and forthright opposition to all forms of militarist ideology. Echoing his 1899 critique of the mystique of “Physical Force in Irish Politics”, the Connolly of the 1916 Rising drew the following line in the sand and added his own emphasis:

“But the moment peace is once admitted by the British Government as being a subject ripe for discussion, that moment our policy will be for peace and in direct opposition to all talk or preparation for armed revolution. We will be no party to leading out Irish patriots to meet the might of an England at peace. The moment peace is in the air we shall strictly confine ourselves, and lend all our influence to the work of turning the thought of Labour in Ireland to the work of peaceful reconstruction … “.

There was nothing of the “anarchist” or “bloodthirsty” caricatures of Connolly to be found in his actual Programme – an eminently pragmatic and practical approach to whatever possibilities existed for ensuring the progress of Irish society and advancing the working class position within it. And yet in all his practicality he never lost sight of a value-system and a vision of an ideal society that drove that practicality forward and gave it purpose. I will therefore conclude with Connolly’s own lines from his poem “Be Moderate”:

“Some men faint-hearted ever seek

Our Programme to retouch

And will insist when e’er they speak

That we demand too much.

‘Tis passing strange, yet I declare

Such statements cause me mirth,

For our demands most modest are:

We only want the Earth!”