Public Private Partnerships are already privatising our public water system

national |

bin tax / household tax / water tax |

other press

national |

bin tax / household tax / water tax |

other press  Monday December 19, 2016 13:00

Monday December 19, 2016 13:00 by 1 of Indymedia

by 1 of Indymedia

We reproducing this article by Dr Rory Hearne, Researcher & Author of "Public Private Partnerships in Ireland: failed experiment or the way forward ?" to highlight some important background and context to this issue

Fears about the privatisation of public water provision was a central motivating factor behind the Right2Water protest movement but concerns about the privatisation of water are held by many other political and civil society groupings. The recently published Expert Commission on Water Services Report highlighted a widespread public “concern about the potential privatisation of Irish Water”. They stated that public responses to their consultation “expressed concerns that water charges, and metering of domestic households, could eventually lead to privatisation”. The Report notes that this “was sometimes set in the context of wider concerns about privatisation of public services, and the commodification of water”. However, it is widely known that various public and private interests have been preparing the ground for the potential privatisation of the Irish public water system. In this article I provide evidence that should concern all those worried about the potential privatisation of Irish public water. This centres on the on-going implementation of Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) in the provision of public water infrastructure in Ireland. These PPPs are a form of ‘creeping privatisation’ that makes the full privatisation of our public water system a real possibility in the future.

This ‘creeping privatisation’ or ‘outsourcing’ of key parts of the public water infrastructure system has been going on for almost twenty years through PPP projects. These PPPs involve private companies providing, operating and managing water and waste-water treatment plants for some of our largest cities and towns. Worryingly most of these private companies are global corporations leading the way in water privatisation internationally. They now control water and waste-water treatment infrastructure such as the Dublin Ringsend Waste Water Treatment Plant, (treating waste water from over 1.7 million people), the Bray/Shanganagh plant (serving a population of 248,000), Sligo (serving 80,000), Waterford (180,000), and plants in Cork, Tipperary, Offaly, Meath, and Donegal, amongst others.

According to Dail records there are, in fact, 115 of these PPP contracts to Design, Build, Operate and Maintain (DBO), water and waste-water treatment plants across 232 sites in Ireland. The contracts are worth a massive total of €1.4bn and most are set to run up to 2030. It is estimated that Irish Water (previously the local authorities) are paying out €123 million per annum to the private companies to cover the operation/maintenance/repayment costs of these PPP contracts.

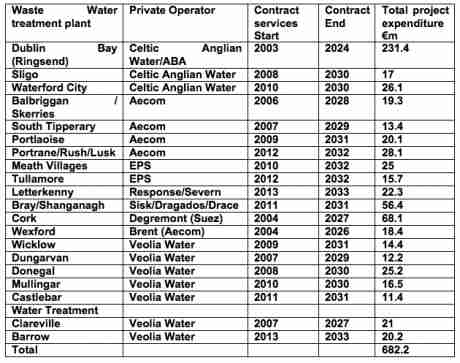

Drawing on figures from the Comptroller and Auditor General, Dail records, and information gathered from the websites of private water companies, I have compiled information on the twenty largest water/waste-water treatment plant PPPs in Ireland. The value of these, at €680 million, is almost half the value of all the water/waste-water PPPs. This information is presented in the table below[i].

Public Private Partnerships introduced in 1999 in Ireland

PPPs were first introduced in the delivery of public infrastructure (schools, motorways, social housing, water treatment plants etc) in Ireland by the Fianna Fail and the PD Government in 1999, following lobbying by IBEC and the Construction Industry Federation. Pilot PPP projects were developed in the delivery of motorways (toll roads), schools, rail (the LUAS), and water and waste-water treatment plants. New PPPs were developed in these sectors through the early 2000s and extended to include social housing regeneration projects.

PPPs are different from public delivery of infrastructure. For example, in 'traditional' public water and waste-water service and infrastructure delivery, treatment plants would be designed and planned in-house within the local authority (and if they required additional finance, also by the Department of Environment), and then either directly built by public labour or, in recent decades, contracted out to a private company to build. Then the infrastructure was taken and managed by the local authority. By contrast DBO (or DBOM as they are also referred to) PPPs involve the ‘outsourcing’ of the entire process, including design, operation and maintenance of the infrastructure, to commercial private water corporations, for contracts usually lasting twenty years. Some PPPs also include the use of private finance to fund the infrastructure (referred to as DBOF PPPs).

In the various National Development Plans in the 2000s Irish governments outlined how they aimed to increase PPPs to 15 per cent of all public capital investment by the end of that decade. In 2012 the C & AG showed that PPPs to the value of almost €8bn had been developed in Ireland, mainly in Schools, Roads and Water/Waste water sectors (figures show that, excluding water/waste water, €2.3bn has been spent on PPPs, and there is €4.1bn outstanding in commitments to be paid to PPP projects).

Ten ways PPPs are privatisation

A major issue of debate and concern about PPPs has been their role in the privatisation of public infrastructure and services. Governments, civil servants and local authorities have been arguing from the start of PPPs that they are not a form of privatisation as there is no ‘asset transfer’ or disposal of assets. For example the DOE stated in 2010 that, “A fundamental principle of DBO’s in the water services sector is that, while the infrastructure is operated under contract to the water services authority, it remains at all times in the authority’s ownership.”

However, the evidence and research (detailed in my book Public Private Partnerships in Ireland, which was based on my PhD research) into the practical outcomes of PPPs in Ireland and across the world proves conclusively that they are a disturbing form of privatisation through outsourcing.

In the early 1990s, particularly in the UK and Latin America, PPPs were promoted by governments, in response to growing public opposition to privatisation, as a new method of public infrastructure and service delivery that did not appear as privatisation. But PPPs, as I will show, actually continue the privatisation and neoliberalisation of public services. They were strongly promoted by New Labour in the UK, and by key international institutions, such as the EU, IMF, OECD and the World Bank.

In the following sections I show ten ways by which PPPs are a form of privatisation of the public water/waste-water system and lead to a further embedding of privatisation, marketisation and commodification processes within the public water/waste-water system.

1.PPPs mean loss of control to global water corporations

Firstly, there is the loss of control over public water and waste-water infrastructure from accountable public agencies (local authorities) to global commercial corporations. Analysis of the data in Table 1 shows that, of these 20 largest PPPs, 90% (18) of the companies were foreign multinationals or Irish subsidiaries of foreign multinationals. This represents a major loss of control over our public water infrastructure. This is nothing short of privatisation. When control over public infrastructure is transferred from the public sector to the private sector, it should be classified as a form of privatisation. The following section provides an overview of these private companies.

Veolia Water Ireland has seven of the largest 20 PPP contracts (35%), at a value of €120 million. These include the two large PPP water treatment plants (Clareville in Limerick and Barrow Abstraction, Kildare) and waste-water plants in Castlebar, Donegal, Mullingar, Wicklow and Dungarvan. But on its website, Veolia explains that it operates many more treatment plants across the country. It states that their “operating contracts provide water-related services for a population equivalent of close to 1,000,000 people in the Republic of Ireland operating more than 30 plants within Ireland, encompassing wastewater, potable water and sludge treatment”. Veolia Water Ireland is a subsidiary of the French multinational company, Veolia, which is the largest private water company in the world. Veolia has global revenue of €24bn and manages 4,245 drinking water plants and 3,300 waste-water treatment plants globally. It also has the contract to operate the LUAS and various private waste collection services. Veolia Water (Ireland) also has non-domestic water metering and billing contracts with a number of county councils.

The company with the next largest share of these 20 largest PPP contracts was Aecom, with five projects (25% of the projects - valued at €99million) including the Balbriggan /Skerries Wastewater Treatment plant, the Rush/Lusk Wastewater Treatment plant and the South Tipperary treatment plant. Aecom (formerly Earthtech Irl) is a multi-billion (revenue of €17.4bn) US multinational engineering corporation. But it combines financing, design, building, and, as it states a “global network of experts delivering water and energy, building iconic skyscrapers, planning new cities, restoring damaged environments, asset management, cyber security operations, education, healthcare, transport.” They are a complete government infrastructure delivery corporation. Aecom has approximately 95,000 employees and is listed on the new York stock exchange.

Next up is Celtic Anglian Water (CAW), which has three projects and operates the largest waste-water treatment plant in the country, the Ringsend Wastewater Treatment Works, which provides secondary and tertiary treatment for a population equivalent of 1,700,000. The contract value is €250 million and runs up to 2022. In 2001 CAW was the first private company to be awarded a contract for the operation and maintenance of a Water Treatment Plant in the Republic of Ireland. It also runs the Galway County Non-Domestic Metering System (including debt recovery, billing etc) – a contract valued at €10.8 million running up to 2018. CAW is a subsidiary company of Anglian Water Group, one of the largest private water companies in England where water is privatised. Anglian made an operating profit in the UK of £452.6 million for 2014/15.

2.PPPs involve privatisation of policy making

Secondly, PPPs involve the loss of control over public infrastructure and governance through the privatization (outsourcing) of the process of policy making including the macro-level analysis of the effectiveness and appropriateness of PPPs as a general policy, the design of frameworks for implementation, and down to the micro-level assessment of Value for Money for individual projects and the design and planning of the infrastructure. One of the major private companies given responsibility for such processes by the Irish state is PriceWaterHouseCooper (PWC) ‘consultants’, one of the big four global auditing, procurement and accountancy firms. PWC have played a central role in advising Irish government Departments to develop PPPs in water and waste water infrastructure. The Department of Finance appointed PWC in 2001 to review the effectiveness of the PPP method and, unsurprisingly, they recommended further expanding the PPP programme. They also outlined the policy framework required to increase the rate of implementation of PPPs in Ireland. PWC were also commissioned by the Department of the Environment in 2001 to develop a framework for PPPs to be advanced in Ireland in the roads, water and waste sectors. PWC also carried out the report in November 2011 for the Department of Environment which advised how Irish Water should be set up (for which PWC were paid a tidy sum of €180,000). They are also involved in evaluating PPP projects on behalf of local authorities and government Departments to assess if they are ‘value for money’ (VFM). The result of their Value for Money (VFM) Public Sector Benchmark calculation provides the justification if infrastructure is to be procured through PPPs or the public sector method. PWC have also been involved in bidding for water privatization across the world, most notoriously in India (where the World Bank was found to have unethically supported them).

There is a clear conflict of interest here as the same private company which promotes PPPs internationally and is set to gain financially from the expansion of PPPs is being used by government and local authorities to advise on the continued use of PPPs and crucially, assess if PPPs provide VFM or not.

3.No meaningful ownership or control held by the state in PPPs

Thirdly, while the state claims they still have the ‘ownership’ of the infrastructure, the reality of PPPs is that when the infrastructure is managed, maintained and operated by the private sector in long term contracts, there is in fact no meaningful ownership or control by the state. The private sector controls the day-to-day operation and thus has control over the knowledge and management of the infrastructure, so in terms of real control and power – the private operator holds it.

This lack of control and the embedding of permanent private control and profiteering is shown by the experience of the Dublin (Ringsend) waste-water treatment plant. Local residents have suffered persistent foul odour problems emanating from the plant due to inadequate design and equipment failure in the plant. There has been an on-going dispute between the responsible local authority, Dublin City Council, and the private operator, Celtic Anglian Water (CAW), over the extent of the problems and who should pay for them. CAW argued that DCC would have to pay for any changes as they would be outside the PPP contract. In the end, DCC paid CAW €35million to address the problem.

This contradicts the theory of PPPs where they are supposed to provide a cost benefit to the state by transferring the cost of dealing with unforseen problems such as this (referred to as ‘risk’) over to the private sector. This case shows that as the private company now controls the project and thus has the core knowledge and skills, it can define the issue, the problem and the cost of rectifying it. It can effectively hold the state to ransom and force the state to pay significant additional amounts to get any changes made. That is unless the state is prepared to sanction and fine the company, or at least stand up to and demand lower costs from it. But the Irish state has shown that it is unwilling to do this because it doesn’t want to stop future companies engaging in PPPs. Its part of the price of having a ‘business friendly economy’. The state (the Irish public) keeps picking up the tab and subsidising the private corporations.

4.When upgrading of infrastructure required PPP contracts will continue to go to private operators

Fourthly, what will happen in future years when upgrading, or capacity extension is required in the treatment plants, or new measures to meet new environmental quality standards outside of the original contract are required and thus renegotiation of the PPP contracts? The private operator will hold the control and knowledge and will be able to charge the state significant premiums to make changes. The case of the West-Link toll road demonstrates this point. When the public sector required changes to the service, it had to pay over half a billion euro to purchase the PPP contract from the private operator so that it could undertake the required changes. Furthermore, who is likely to get the new contracts for upgrading infrastructure? A new private company or the state itself? The problem with the PPPs is that the private operator effectively holds a form of monopoly position and thus it is likely to get it. The is shown by the fact that CAW was awarded a further DBOM contract to upgrade the Sligo Plant by Irish Water in April this year.

5.PPPs make private outsourcing of our public water/waste water infrastructure permanent and full privatisation more likely

Fifthly, what will happen when it comes to the end of the PPP contract life in fifteen to twenty years time? Will the plants, as the state claims, revert back to public ownership when the contract ends? This is very unlikely if we continue down the PPP outsourcing path when we have run down and further diminished the capacity of local authorities to manage our water and waste water infrastructure. It is more likely to stay in the control of private operators into perpetuity. This shows how PPPs make private outsourcing of our public water/waste water infrastructure permanent and thus are likely to lead to a continued and deepening privatisation and contracting out.

This is also shown by the fact that DBO PPPs appear to be the only option being made available to (and preferred by) local authorities (now Irish Water) and there is no longer a public sector alternative being made available. Thus PPP privatisation is the only option for upgrading and providing new water services infrastructure. The 2010 Department of Environment Report on the Value for Money for Review of the Water Services Investment Programme 2007-2009, states this explicitly:

“in the case of water services infrastructure, the DBO model is the preferred procurement route in the case of works involving the provision of treatment plants subject to completion”. This review also recommends deepening private involvement further by involving private finance “in the future in relation to some large scale projects”.

Therefore existing PPPs lay the foundation for the further development of PPPs in this area as is shown by the trend towards the increased use of PPPs over time. Getting private companies into design, build, operate and manage the water/waste water infrastructure is thus the thin edge of a wedge that opens up the potential for complete privatisation.

The private companies themselves highlight this as they use their existing contracts to try get more PPPs. Veolia explains how they “leverage the experience, stability and geographical coverage” of their existing 20-year PPP contracts in order to “offer present and future customers a cost effective outsourcing solution”. While CAW is even more bold in their ambitions stating that they aim “to become the leading water and waste water service provider in Ireland”. Is that not the complete private corporate takeover of the public water infrastructure system?

Ultimately these DBO PPPs make it even more straightforward and easier (and thus more likely) to privatise water/waste water infrastructure in the future because the only ‘public’ aspect remaining to be privatised is the official ‘ownership’ of the infrastructure. It is only a Minister’s signature away from the sale and complete transfer to the private sector.

6.PPPs ‘commodify’ and ‘marketise’ public infrastructure

Sixth, PPPs also ‘commodify’ and ‘marketise’ this public infrastructure by creating a new ‘market’ in the provision of public water/waste-water infrastructure, through the conversion of the entire process of the provision of public water/waste-water infrastructure into a ‘contract’ which is a tradeable ‘asset’ or ‘commodity.’ They thus open up public infrastructure and assets as income generating opportunities for the private companies.

For example, EPS, one of the Irish private water companies that has two waste-water PPP contracts (and an annual turnover nearing €70 million) explains how they have been “at the forefront of the development of the Irish water market through successive National Development Plan cycles” and they “have nurtured a market leading share of the Design-Build-Operate (DBO) market in Ireland”. Similarly Celtic Anglian Water refer to the public infrastructure as an ‘asset’. CAW explains that it operates “in the development of water and wastewater assets - providing water supply, wastewater treatment, plant operation and maintenance services”. So these private water companies are quite clear how PPPs are a ‘marketisation’ or market-creating process of commodifying public water/waste water infrastructure.

And make no mistake about it, water/waste-water infrastructure provision is a massive potential market. There are approximately 973 public water supplies and approximately 500 waste water treatment plants in Ireland. That means that based on 115 DBO contracts, approximately 20% of our waste water treatment plants are already part privatised/outsourced. And given the need to upgrade treatment plants to meet environmental quality standards major investment is required into the future in treatment plants. You can also add upgrades and improvements required for the entire water treatment network on top of that. We can see therefore how this whole area is a potentially very large and lucrative future market for the private water companies. And this requirement to upgrade this infrastructure such as water and waste water treatment plants is being eyed up as a big opportunity for profit by many companies. The Irish Times reported earlier this year that “The Denis O’Brien-owned industrial services group Actavo is likely to seek more work from State utility Irish Water… as the State utility moved ahead with plans to renew the Republic’s water treatment and supply systems, Actavo would bid for contracts to work on the various projects that this is likely to involve”.

7. Water infrastructure becomes commodities traded on financial markets-no democracy

Seventh, further marketization takes place as the PPP contracts themselves are a tradeable commodity on financial markets. PPP contracts and companies are bought and sold for profit all the time on financial markets and international asset markets, between various private equity investors, hedge funds, and corporations. They are often loaded with debt from other companies and then ‘asset sweating’ is undertaken whereby the new owners (financial speculators) don’t invest in the project but extract as much profit as possible (through, as I later explain, reducing quality of service, workers pay and conditions, increasing user charges, increasing the cost charged to the state etc).

As I wrote in my book this also has implications for the democratic provision and accountability of public services: "The process of buying and selling public assets as internationally traded commodities could have significant implications not just for the provision of public services and infrastructure, but for the democratic control by national governments over the services for which they have the responsibility to provide to their public."

8.PPPs do not provide Value for Money as profits extracted by private sector

Eighth, PPPs are also a deeper form of privatisation than simple public asset sales because they involve the on-going subsidisation of private corporations by the state and the public (through contract fees, tolls, user charges) for decades through the PPP contracts. Thus PPPs provide huge profits to the private corporations. Take Veolia Water Ireland, for example, it increased its revenue from €36.6 million in 2014 to €40.3 million in 2015. Their profit was €0.8 million in 2015 and €1.2 million in 2014. Financial data for CAW shows that in 2015 it had €30.1 million turnover and made €4.4 million in profit (in 2014 it made €6.6mil in profit). That’s just two companies and based on Dail figures private water/waste water companies are receiving a revenue of at least €123 million a year from the Irish tax payer.

This profit extraction is a key part of the explanation of why PPPs are actually more expensive than traditional delivery. How can they provide VFM when huge profits are being extracted? This is a significant additional cost that is not included or measured in the VFM calculations. This ‘asset’ grab by private corporations is a loss of resources and value for the Irish public as they have to pay for this profit, which does not exist to the same extent in traditional public procurement (provision) of water/waste-water infrastructure.

Dr. Vandana Shiva has written about this in relation to the privatisation of Delhi’s water supply in India through a PPP water treatment plant operated by Ondeo Degremont (a subsidiary of French company Suez Lyonnaise des Eaux Water Division—the water giant of the world):

“Suez is not bringing in private foreign investment. It is appropriating public investment. Public-private partnerships are, in effect, private appropriation of public investment. But the financial costs are not the highest costs. The real costs are social and ecological”. Interestingly, Ondeo Degremont constructed (and is possibly still operating) Corks largest waste-water treatment plant.

The Comptroller and Auditor General has found that PPPs are 8-13% more expensive than traditional public procurement. Reeves (2011) found that for a number of water based PPPs the initial estimation of VFM under PPP was revised downwards from 9.5 per cent to 0.8 per cent (of whole-life cost under traditional procurement) following consultation with stakeholders including trade unions. In another case Reeves (2013) shows that after consultation, estimated VFM was revised from 2.3 per cent in favour of PPP to 2.25 per cent in favour of traditional procurement. These revisions were attributable to a number of shortcomings in the original VFM analyses including the omission of relevant costs including: (i) costs incurred following the re-deployment of existing labour if PPP was adopted; (ii) transaction costs; (iii) and the costs of monitoring and supervising the PPP contract over the 20 year period.

There is another democratic deficit at the heart of PPPs which links to their inability to prove they provide Value for Money. The Public Sector Benchmark (PSB) VFM calculation (often carried out by pro-PPP companies like PWC) is not available for public analysis due to ‘commercial sensitivity’. Yet this is the key evidence that justifies PPPs- but we cannot see it. Therefore there is no evidenced way of showing these projects actually are value for money.

9. PPPs involve reduction in worker’s pay, conditions and rights.

The ninth way in which PPPs are a form of privatization is the reduction in worker’s pay, conditions and rights. A key method by which PPPs are used to ‘reduce’ costs is through such a reduction in the conditions and pay of employees. As with other forms of privatisation and outsourcing PPPs have been associated with a degrading of worker’s conditions and, in particular, a tendency to refuse trade union recognition. For example, in 2013 it was reported that an employee in the Shanganagh PPP Waste Water Treatment Plant was dismissed 'for trade union organised activity’. Workers there organised a strike as the employers refused to recognise the trade union and there were other issues around fair pay for hours and shifts worked. The private operator of the PPP plant is SDD Shanganagh Water Treatment Ltd, which is a joint venture between the Irish construction company, Sisk, and Spanish companies Dragados and Drace. However, the workers were, in fact, employed by a separate subcontracted agency. Thus we see how PPPs further the process of the casualisation and downgrading of worker’s conditions and undermine and reduce hard-fought rights and conditions of public sector employees such as trade union recognition and collective bargaining. Through PPPs it is the state (which, of course, should be protecting and promoting worker’s rights) that is playing a central role in driving down worker’s conditions.

10.PPPs support water charges and furthers privatisation

The tenth and final way PPPs support privatisation is their promotion and support for user charges such as water charges and the way in which this furthers the privatisation process within the water system.

The introduction of user fees/charges for public services has been central to the neoliberal policy agenda which is about convincing the public to accept that they have to pay for public services through user fees, even if they were previously paid for from general taxation and were free at the point of delivery.

PPPs have already facilitated the introduction and intensification of this policy through the introduction of user fees for toll roads. The Irish state has supported this process of profiting from PPPs. In one of the interviews in my research a senior civil servant working in a Central Government PPP unit told me that ‘it has to be a quid pro-quo that the private sector gets profit, while it might cost more for the user. There has to be profit, otherwise it doesn’t work.’

Indeed, the Irish government has promoted the ‘unlimited’ potential for the development of PPPs funded by user fees. Assistant Secretary of the Department of the Taoiseach, Mary Doyle, speaking at the 3rd Annual PPP Policy Forum (2007) explained that, ‘since Ireland is the home of the entrepreneur there is no limit on any projects that can be undertaken by PPP where they are funded entirely by using charges’. The roads, schools, waste and water/waste-water sectors demonstrate how, because the private sector required an income stream (profit) as the basis of its involvement, the use of PPPs necessitated, the commercialisation of, and private-capital control over, public resources and assets. As a representative of the Department of Environment explained to me in an interview:

“The private sector may be able to generate additional revenues from third parties, thereby reducing the cost of any public-sector subvention required. Additional revenue may be generated through the use of spare capacity or the disposal of surplus assets”

Through the application of these ‘income-generating mechanisms’, PPPs facilitate the implementation of a central neoliberal policy objective of creating ‘unlimited’ market opportunities for the private sector within public governance, services and infrastructure (Bourdieu, 1998; Brenner and Theodore, 2002; Harvey, 2005; Whitfield, 2006).

And, as we see more and more PPP contracts made by Irish water –this increases the financial commitment to PPP companies and, thus in the future, an argument could be made for introducing and/or increasing water charges in order to pay for these contracts with PPP companies. A ‘revenue stream’ will be required to pay the private operators. Thus PPPs open up the argument and requirement for the introduction/increase of water charges and the introduction of water charges opens up, and provides, the revenue stream to pay private operators. PPPs and water charges are, therefore, a mutually reinforcing process as the introduction of one leads to arguments in favour of the necessity of the introduction of the other. And they both provide key steps towards the further privatisation of the Irish public water system.

Conclusion

Overall then we can see from the evidence presented here the dangerous amount of power and influence that global corporations are being given through PPP projects in the water/waste-water infrastructure in Ireland, and the way in which the state is actively facilitating this neoliberalisation of water governance. Private corporations, facilitated by the Irish state, are imposing their corporate model as the future for government and public service and infrastructure delivery. It is a dystopian future for citizens whereby private corporations will provide and profit from (and speculatively trade on financial markets) all aspects of government including public services and infrastructure – through highly profitable contracts paid for by nation states and local government. It is the ultimate privatisation and commodification of all public goods and infrastructure. This is the neoliberal project laid bare. What David Harvey describes as “accumulation by dispossession.” It is about taking the resources (and assets) away from state public services and infrastructure which benefit the working and middle classes and instead funnelling them to the wealthy and private corporations. PPPs are playing a strategic role in this process of capturing public services and assets for private investment and wealth accumulation. The global and EU trade liberalisation rules and new treaties such as CETA and TTIP also support PPPs by further obliging national governments to ‘liberalise’ markets for services and infrastructure on a global scale.

An excellent article critiquing the impact of PPPs and water privatisation in India describes the process of privatisation through PPPs which can also be applied to the Irish case:

“But whatever the nuances, although formal ownership continues to nominally vest with public entities, all these “public-private partnerships” are undoubtedly different forms of privatization, with public bodies ceding varying degrees of control over quantity, quality, coverage and pricing to corporate bodies. Since the private party is in the business for profit, water in such privatized utilities is always viewed, valued and managed in terms of its price. Whatever the specific form of involvement of private players, water moves from being a common good to a commodity, with all that this implies”.

The evidence shows, therefore, that PPPs are a complex form of intensive privatization, marketization and commodification of the Irish public water and waste-water infrastructure system. Private-sector involvement has not guaranteed a better-quality service and additionally, the private operator’s profit maximisation requirements has resulted in the running down of service quality, workers conditions and turning the assets into commodities to be profited from. They ensure big profits for global water and ‘governance/development’ corporations and financial investors and rising costs and ineffective services for public service users, and the erosion of workers’ rights. Thus they contribute to the exacerbation of economic inequality.

The values and ideals of social rights that inform public-sector values and priorities are undermined by the market ethos of PPP policy making. Under this process, public service users are converted into ‘clients’ and ‘consumers’ and a ‘revenue stream’. All of this evidence shows how the pursuit of PPPs are an ideological policy. The evidence does not support the use of PPPs in public water and waste water infrastructure provision. They are being pursued principally because of policy maker’s adherence to (and belief in) neoliberal privatisiation policies rather than any evidence based justification.

Remunicipalisation

In recent years governments and local authorities across the world, in response to the failure of water privatisation such as increased water charges and poor service delivery by the private companies, and under pressure from citizen campaigns asserting the human right to water, have started a process of ‘remunicipalisation’ – taking water and waste-water services back into public management. Our public water future: The global experience with remunicipalisation, a book published last year shows the growing wave of cities putting water back under public control – with 235 cases of water remunicipalisation in 37 countries, affecting over 100 million people, between 2000 and 2015. The number of cases doubled in the 2010-2015 period compared with 2000-2010. France, a country that spearheaded water privatisation and PPPs has lead the way with 94 cases of remunicipalisation. Also recently a large majority of the Barcelona City Council voted to end the private management of water and support the remunicipalisation of the water service in of Barcelona. Barcelona En Comu, the new citizens movement who holds the Mayorality of Barcelona, promoted the measure as it was one of the most popular among citizens in their participatory process carried out to define the Municipal Action Plan (the plan that guides city policy). Barcelona En Comú, believes that water is a human right, a basic service and a common good that should be under public, democratic control.

Slovenia also recently amended its constitution to make access to drinkable water a fundamental right for all citizens and stop it being commercialised.

The new article in the constitution reads that “Water resources represent a public good that is managed by the state. Water resources are primary and durably used to supply citizens with potable water and households with water and, in this sense, are not a market commodity.”

It was reported in the Guardian that the Slovenian Prime Minister encouraged the change because: people should “protect water – the 21st century’s liquid gold – at the highest legal level”…and that “Slovenian water has very good quality and, because of its value, in the future it will certainly be the target of foreign countries and international corporations’ appetites…As it will gradually become a more valuable commodity in the future, pressure over it will increase and we must not give in”. Slovenia is the first European Union country to include the right to water in its constitution, while 15 other countries across the world had already done so.

The on-going implementation of PPPs shows that the Irish public water system has already been part-privatised/outsourced and without a change of direction and policy it is in danger of being further marketised and privatised. This lends support to the case being made for a Referendum that could enshrine the Irish water system as a public good and human right in the Constitution and thus provide a constitutional guarantee on the public ownership of our water. The Expert Commission found that the most commonly expressed preferred method for confirming Irish Water in public ownership “was by a constitutional amendment”, and that the provision for a plebiscite, as provided for in the existing legislation “did not provide the necessary level of guarantee.”

Right2Water has proposed the following wording that could be inserted into the Constitution to enshrine this:

“The Government shall be collectively responsible for the protection, management and maintenance of the public water system. The Government shall ensure in the public interest that this resource remains in public ownership and management.”

The passing of such a referendum is an essential step in stopping the full privatisation of our public water system and, in particular, would put a halt to the back door creeping privatisation of through PPPs in water and waste-water infrastructure and support the remunicipalisation (taking back into public control) of the existing PPP water projects.

Sources:

Hearne, R. (2011) Public Private Partnerships in Ireland: failed experiment or the way forward? Manchester University Press Available at: http://www.academia.edu/30178583/Trends_in_historical_d...cture

Hearne (2012) http://politico.ie/society/public-private-partnerships-...rward

Hearne (2009) Origins, Development and Outcomes of Public Private Partnerships in Ireland: The Case of PPPs in Social Housing Regeneration Dr Rory Hearne http://www.combatpoverty.ie/publications/workingpapers/...PPsIn...

Alan Kelly, 28th April 2015, Dail Eireann, https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2015-04-28a.1222

Comptroller and Auditor General (2016) Briefing Note on PPPs

https://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/p...42-B-(B)---Briefing-Note-on-PPPs-from-CAG.pdf

Comptroller and Auditor General (2011) Annual Report http://www.audgen.gov.ie/documents/annualreports/2011/r...1.pdf

Irish Times (2008) Report recommends upgrade of Ringsend waste plant

http://www.irishtimes.com/news/report-recommends-upgrad...d-was...

Hell Bent on Water Privatisatin in Dehli (http://newsclick.in/india/hell-bent-water-privatization...delhi)

Oireachtas (2013) Public Private Partnerships Data, July 2013,

http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/Debates%20Author...00112

Reeves, E. (2014) Public Capital Investment and Public Private Partnerships in Ireland 2000-2014: A Review of the Issues and Performance

https://www.socialjustice.ie/sites/default/files/attach...s.pdf

Shiva, V. (2006) RESISTING WATER PRIVATISATION, BUILDING WATER DEMOCRACY, http://www.globalternative.org/downloads/shiva-water.pdf

The 2010 Department of Environment Report on the Value for Money for Review of the Water Services Investment Programme 2007-2009

The Guardian (2016) Slovenia Adds Water to Constitution https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/nov/18/slo...ater-...

[i] I have not, as of yet, been able to gather data on the other 95 water/waste-water DBO PPP contracts because they are of a smaller individual value and have been undertaken directly by local authorities with little input from the Department of Environment. Therefore the C & AG does not provide the same level of detail on these projects.